[2,107 words]

This week, we’re presenting you with a book review, written by one of our recent slush readers and Pushcart nominee, Amita Basu.

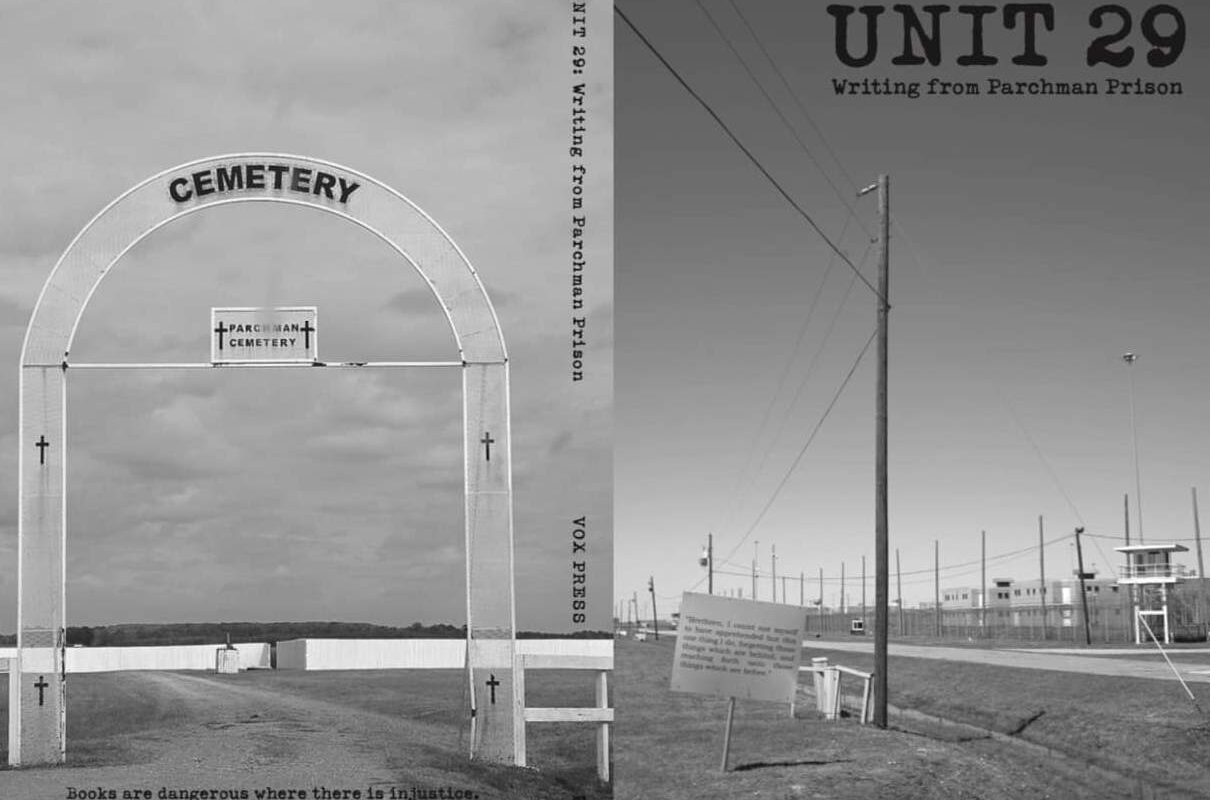

Published by Vox Press, Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison, is a collection of writings and art from incarcerated men living in Unit 29 at Mississippi State Penitentiary who tell their own stories about their experience in one of the country’s most notorious prison facilities.

I wanted to highlight this book because it’s important to me to uplift marginalized writers. Writing and storytelling is such an accessible art form, which is one of the reasons I love it so much. The point of art is to communicate and in this book, the inmates communicate their realities, which are experiences that are often overlooked.

As Amita mentions, there is hope in this book. And hope is also apparent in the existence of this book. Being able to share one’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences is so much more meaningful and healing when you share it with others and when you know they hear you. That’s why, to me, this book is hopeful: because it provides an avenue for connection. When we begin to recognize ourselves in others, and vice versa, we can start to break down the divide. We learn how to take care of each other and to celebrate the things that connect us, like the ability to create beautiful art.

One thing that stood out to me in this collection was the varying styles the authors chose to employ, from poems in different formats to drawings to essays. It’s evident that there is no lack of talent in this group of creators. As Amita mentions below, the work is incredible, and I hope you, our readers, will take a chance on this book.

Elena L. Perez

Editor in Chief

Darkness and wit, delusion and hope: Parchman Unit 29 offers glimpses from lives of squandered opportunity, and lives that maybe never had much of a chance. These poems, drawings, and creative non-fiction pieces constitute a powerful call for systemic reform and for compassion towards those less fortunate.

Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison is the most difficult book I’ve ever read. Dostoevsky’s books come close, as, interestingly, does Sartre’s Nausea. An oppressive atmosphere hangs over all these books, a miasma of inexorability perhaps most accurately called tragedy. What could be more tragic for a human being than an indefinite loss of freedom? For Nausea’s Roquentin, his prison was self-created; on the book’s last page he begins to transcend it. For the poets, writers, and visual artists in Unit 29, escape, if it exists at all, often drives them inwards: to the Christian God, to Wicca, or to a belief in their own resilience.

I’d originally intended to write a scholarly review, placing this book within the larger context of injustice and abuse in the American prison system. This book has in fact roused my curiosity. I continue to read about the ethical and practical problems of carceral punishment, the experiences of inmates, and the prison reform movement. But the most honest review I can write of Unit 29 – as someone who’s not American and has never known an incarcerated person – is perhaps a purely personal response.

The circumstances of unfreedom detailed in these thirty writers’ and artists’ work are often incredible. One of Unit 29’s writers taught me that “shit-flinging” is a literal descriptor for an activity to which frustrated or psychologically disturbed inmates often resort. Inmates also find ways to set fires in their cells, flooding the unit with toxic smog which hundreds of others are forced to inhale. Toilets jam and flood, or bring up what’s been flushed down in another cell. Though technically living indoors, inmates are subject to extremely inadequate heating and cooling. They seem as exposed to the elements as if they were living in the open. Unit 29 offers glimpses lived totally at the mercy of correctional officers (C.O.s), wardens, and other inmates (including “organisation members” – a euphemism, I learned, for “gang members”).

It’s bewildering to imagine being exposed to every sort of corruption and insanity, to nature’s indifference and human brutality, and to have nowhere to run. I kept imagining a cruel child, perhaps himself hard done by, trapping a bird in a tiny box, pouring all sorts of noxious things into this box, and chortling with glee.

This book offered me my first extended glimpse into the psychology of a long-term prison inmate. I began to understand the sometimes destructive or self-destructive behaviour that such circumstances can engender. There are references in Unit 29 to sexual assault of another inmate, repeated exhibitionism by inmates (targeting female C.O.s), inmates being beaten to death or starved into inanition, and suicide. Psychological disturbance of every kind and degree is also plain on the page. Physical disturbance is also plain. For instance, a few writers mention spending increasing amounts of time in bed. (The reader infers physical weakness, inadequate nutrition, or undiagnosed illness. There exists one medical doctor for 800 inmates.)

The book’s dedication tells you that one of these thirty male inmates, Christoper Smith, ended up dying ‘by his own hand and by his own will.’ The book features five or six pieces by Smith, well spaced out between fellow contributors’ offerings. Each Smith piece is a series of diary entries. Like many other of Unit 29’s contributors, Smith is in long-term solitary confinement (a.k.a “the Shoe,” S.H.U., or Solitary Holding Unit). Long-term solitary confinement is known to cause drastic mental harm. Smith complains of reverse racism – being white on the inside, he claims, makes you vulnerable, given that the population of inmates and C.O.s at Parchman is primarily black. Smith rejects Christ and wants to worship the Wicca. He demands access to Wiccan books in his cell. He claims his meals are being withheld by a guard who’s got it in for him. Then he goes on a hunger strike. As I read the book, my dread rose with each piece by Christoper Smith. His diary traces a steady decline. His paranoia and rage crescendo, finding vent in extended outbursts in bold and all-caps. When I finally read Smith’s last diary entry, I felt almost relieved that he’d found a way out of this long, dark hell.

I’d heard jokes before, about how, apparently, every convict insists he or she didn’t do it. But only one or two of Unit 29’s writers claim innocence. Several others admit they’re guilty of the crime they were convicted of. Of these, in turn, some claim they’re glad of this time away to think, learn, and grow. Only a few of Unit 29’s contributors talk about their crimes in any detail at all. Some of these crimes appear to have involved drug offences that should, perhaps, more appropriately have been treated with time in a substance abuse facility. Sometimes, a violent crime occurred almost by accident.

It’s terrible for a human being to lose their life. And it’s right that the perpetrator should face legal consequences. But I often found myself reflecting that the currently incarcerated individual seems simply to have been in the wrong place, at the wrong time – with a gun. Often sentenced to life without parole (LWOP), the perpetrator, too, essentially loses his life. So it’s two human lives lost, sometimes thanks to a mistake or accident that took just a few seconds.

As a non-American, I needn’t dwell on the fact that people outside America are astonished by the proliferation of, and easy access to, firearms in the United States. Even as a non-American, as I read the poems and stories of Unit 29, I found myself repeatedly thinking, ‘There, but for the grace of God, go I.’

And I’m an atheist.

I’m also a whiner. But, reading Unit 29, I often found myself counting my blessings.

Several pieces are by individuals who clearly failed to complete even primary school. Several others have pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, but they speak at length – and quite casually – of terrible home environments. One writer mentions stumbling in, as a kid, on his mother and uncle doing hard drugs. The grownups’ response was to invite the kid to join them. Other inmates describe how they’ve let down their families so often that those ‘on the outside’ have moved on: either they no longer accept phonecalls, or conversations are brief and superficial and there’s audible relief when the inmate says ‘Goodbye.’ Inmates express self-loathing at their awareness that close relatives on the outside are ailing and struggling to make ends meet, and at their own inability to help. They express outrage at the irony that they, who have committed a crime, are housed and fed, whereas their innocent relatives on the outside must fend for themselves as best as they can. Inmates wonder if their sons at home have forgotten them. They curse at girlfriends who have deserted them. They indulge in extended fantasies about Spanish soap-opera stars becoming their girlfriends someday.

I find hard books like Unit 29 rewarding. First, because I believe all good art challenges you, your preconceived notions, and the social order. If it’s not doing that, it’s not art, it’s kitsch, to use Kundera’s ontology. Second, because a hard book reminds me of all the things in my own life that I sometimes take for granted. Not just my freedom and happiness, but, more importantly, all the circumstances that set the stage for my freedom and happiness.

We all labour under the agency bias. We vastly overestimate the degree to which our own choices determine our outcomes in life. In fact, the lion’s share of these outcomes is attributable to factors beyond our control. As behavioural geneticist Robert Plomin puts it, the zipcode we’re born in determines which school we go to, and also reflects our parents’ wealth. These two factors are the single biggest influences on where we end up in life. We attribute our success and health to our own willpower and talent. In fact, these and other key outcomes are largely determined by luck and genes and other factors nobody could claim credit for.

This is not to argue that we shouldn’t all try to make better choices. Agency does matter. This is to argue that we should acknowledge how big a role luck plays in our own freedom and the unfreedom of some of our fellow human beings.

The systemic injustice and oppression of the prison system reflects inequities that run in faultlines through the whole social order. In a sense, then, the tragedies that lead to prison and that unfold there are only the visible tip of the iceberg. A lot of the original ugliness lies just where these men turn their hopeful, sometimes desperate eyes – on the outside.

Of course, it’s not all dark. Some of Unit 29’s artists and writers offer witty acrostics and hopeful drawings of doves inside bars. Some seem to conjure determination, hope, and discipline in the face of all obstacles. Others find comfort in God. One prisoner, who sounds otherwise coherent and rational, develops at great length his conviction that he is the devil incarnate. He’s convinced God hates him. After lengthy debates, he renounces God in turn. Another prisoner has been self-publishing books and even, via contraband mobile-phones, posting videos on pseudoscientific topics on YouTube. Yet another writer boasts of a unique skill. Mobile-phones, he says, can be had in prison for a price. (So can anything else. Many of the staff seem to be drastically underpaid, open to all sorts of corruption.) But, sometimes, there’s a raid. Then, inmates must shove all contraband up their backsides. This particular writer describes, quite seriously, how it’s in prison that he has discovered his particular gift: his rear end’s great amenability to the receipt and temporary storage of forbidden goods.

Maggoty food and missing meals. Icy cells and dangerous cellmates. C.O.s who organise an opportunity for other prisoners to stab you to death. Dangerous drugs being sneaked in. (One inmate refers to a liquid drug that’s poured onto a sheet of paper, smuggled in, and sniffed, producing dangerous effects. Then there are bath salts and spice which can also be sniffed. Plus the usual street drugs.) Life in Parchman Prison reads like something out of dystopian science fiction, or perhaps historical fiction. And all this happening to millions of people worldwide. Like all the best art, Unit 29 leaves the reader with a resolution to change something: if not to unite and demand reform, then, at least, to regard with a little more compassion those whose worst crime, perhaps, has been to be born less lucky than ourselves.

Amita Basu’s fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in over sixty magazines and anthologies including The Penn Review, Bamboo Ridge, Another Chicago Magazine, The Dalhousie Review, and Funicular. She is a submissions reader and review board member at Bewildering Stories, contributing editor at Fairfield Scribes Microfiction, interviews editor and sustainable living columnist at Mean Pepper Vine, and slush reader at The Metaworker. She lives in Bangalore, has a PhD in cognitive science, works in sustainable behaviour, and blogs at http://amitabasu.com/.

Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison is published by Vox Press and can be purchased on their website or on Amazon.