Prologue to a Memoir Based on Love Letters to my Dead Husband

By Margaret S. Mandell

Sunday, December 10, 2017

My Dearest Love:

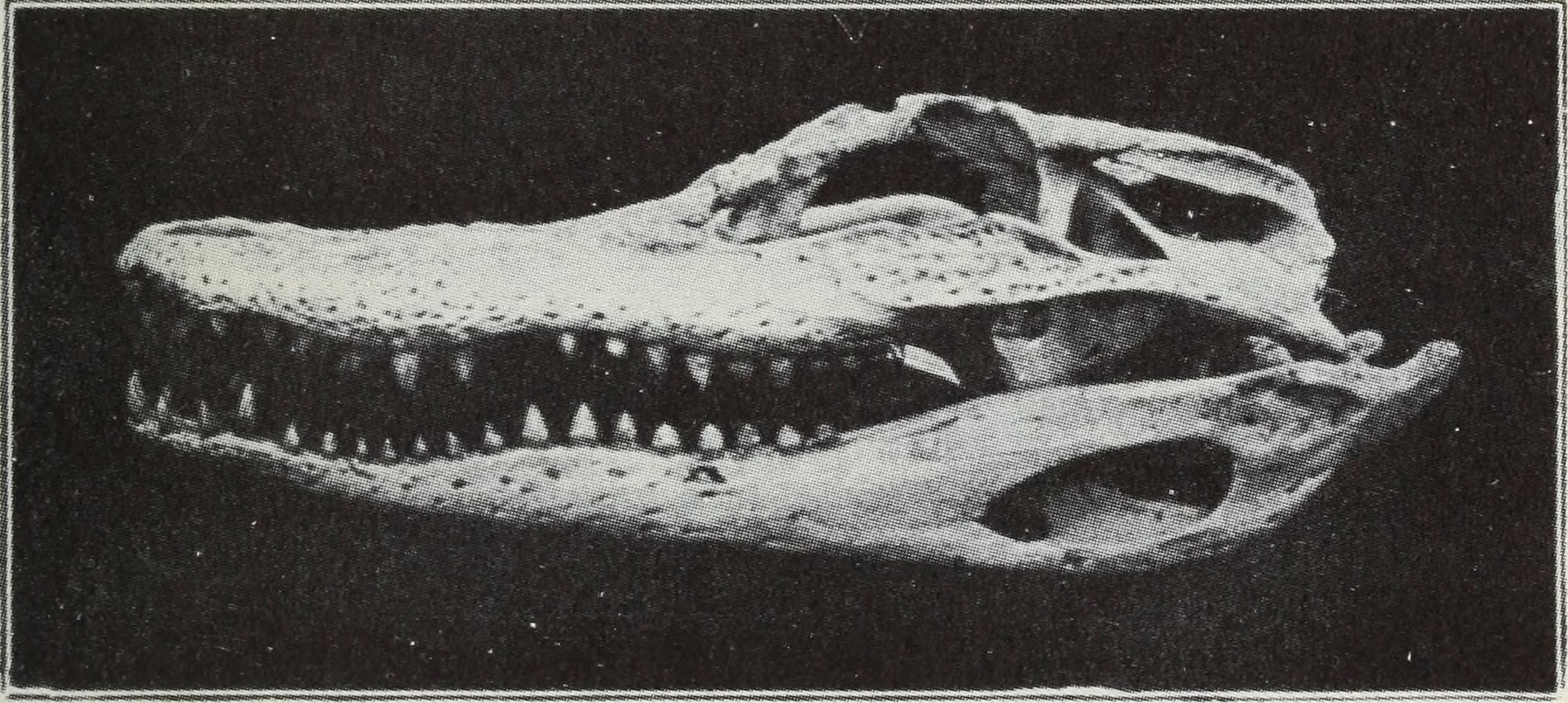

October 2015. I am swimming laps alone in my brother’s infinity pool in Kiawah, South Carolina. Alligators sun themselves on the golf course by the muddy moat three feet below the pool, next to a sign “Beware of Alligators.” You are inside the house. When will you come outside and join me? I think.

We used to swim side by side across Sengekontacket Pond. A mile wide, and I never let you out of my sight. Before the wracking cough started.

Suddenly you appear by the edge of the pool, all six feet of you, chiseled, long-limbed and lean. I pause dripping, grasping the ladder directly below you, squinting into the sun at your handsome silhouette.

“I know what I have,” you say. “I’ve been researching my symptoms all morning on the Internet. It’s worse than cancer. There is no treatment, no cure. Pulmonary fibrosis is fatal. In a few months my lungs will turn to Velcro. I will suffocate.”

You turn and walk away.

I turn and resume swimming laps.

In medical school, years before you became a psychiatrist, you came home one day and said to me, “Today our teacher told us all we needed to know:

‘Listen to the patient–nine times out of ten you’ve got the diagnosis right there.’”

Monday, December 11, 2017

My Dearest Love:

You loved her. I loved her. Before the cough, we both loved yoga with Maryann. Like you, she had large, empathic brown eyes and a smile that radiates:

You’re the only person in the room.

You could tell she was a dancer. She floated in and out of poses like a ballerina. She would sashay into Studio A with the mirrors on three walls, clutching her coffee and exclaim, “Wow! Twelve people at 6 am!” Men, including you, were attracted to her full-figured body and cherubic face framed by a halo of thick black curls.

“Find your e-e-e-e-e-edge,” she intoned, “There it is!” You loved it when Maryann said, “Thank yourself for taking care of your body. Thank your body for taking care of you. Namaste.”

She affirmed all your hard work to stay healthy–eating well, working out, zero body fat–a point of pride with you. Remember in college how your best friend called you “my-body-is-a-temple-Herb”? Most of all, you were lured by the sound of Maryann’s voice, full-throated and hypnotic.

We all were.

Three months after our trip to Kiawah, you sat at our kitchen table, brow furrowed in thought, your body wracked with pneumonia. Out of the blue, between coughs, you said hoarsely,

“Thank myself for taking care of my body? I think I could have taken better care of my body. I was such a workaholic.”

Yes, my love, you were.

Tuesday, December 12, 2017

My Dearest Love:

Do you remember what you said at dinner that night in December 2015 after you were too sick to leave the house?

“This is not what you signed up for,” you said.

You’re dying and you’re thinking of me? I thought.

“This is our love story,” I said, “there is no place else I’d rather be.”

“What do you want for your birthday?” you asked.

“The only thing I want I cannot have,” I said.

Tuesday, January 9, 2018

My Dearest Love:

Our last hug. January 2016.

I had no idea how much I’ve craved your warm embrace since then.

We stood in the kitchen by the fridge, your lungs already at 25% capacity. By then you panted all the time. I held you close, smelled your Old Spice deodorant, felt your long, still strong arms around me and the straining muscles in your chest. I listened to your rapid inhalations, exhalations, breath shallow, struggling.

“I am really dying,” you whispered, lungs crackling like Jiffy Pop in the microwave. Pop, pop, pop.

“But you are here right this minute,” I said, drinking you in, holding on for dear life as if I were the one who had to leave. The fridge hummed.

Friday, January 19, 2018

My Dearest Love:

On this, the second anniversary of your last day alive, I re-read your final words as written in the hospital on January 19, 2016, when you could no longer speak but had so much to say.

“I tried to be a good provider,” you said hoarsely just before they covered your mouth and nose with the oxygen mask. I nodded, swallowing hard. I could see you were suffocating, struggling to speak. You gestured for pen and paper, right hand writing in the air.

“No Temple!” you scribbled frantically in all capital letters on the legal pad I gave you, terrified they were going to ship you out of Abington and back to Temple University Hospital where you were undergoing evaluation for a lung transplant.

“No Temple!” I said, smoothing your crumpled sheets. You told us the day before in the ER you wanted to die right there in Abington Hospital, where you had your first job out of residency and where our daughter was born.

“Left foot itches,” you scribbled on the pad.

I watched your face through the oxygen mask as I scratched the sole of your left foot, wondering how I would know when the itching had stopped. Do you remember how I massaged your feet night after night with those lavender scented Ayurvedic creams after your knee replacement?

“It feels so good,” you always said.

This time you gave no signal.

A few hours later, at 9:30 pm, your breathing slowed and stopped. Your jaw shuddered, then was still. As your heart monitor flatlined, I kept whispering into your ear, “Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you,” thinking if I said it enough times, you would hear me. Your ear was still warm against my lips.

It was Tuesday.

First, I called the kids, who an hour before had kissed you goodnight and left expecting to see you the next day. Lydia, already back in Center City, erupted into explosive sobs. I could see her small frame doubled over, convulsed in agony. Daddy.

Dan, about to go to bed in our house after staying up the previous night by your side, took an Uber back to the hospital as soon as I called. He dragged over the blue Naugahyde chair and sat by your right shoulder, gazing at your gaunt, ashen face. He turned to me and said, “Dad looked death right in the eye.”

Next, I called Rabbi Josh, who had already prayed at your bedside earlier in the day. You could no longer open your eyes. I imagined you could hear his comforting words over the grinding whoosh of the bipap machine forcefully pumping air into your spastic lungs. “Could we please, please, please have Herb’s funeral at the synagogue?” I pleaded over the phone.

I went home and crawled into your side of the bed.

Friday, at your synagogue funeral, I clung to our children and stared at the floor.

Friday night, a blizzard dumped twenty-two inches of snow on Philadelphia.

Saturday, we shoveled the front walk without you.

Saturday, January 20, 2018

My Dearest Love:

I remember yelling at the flowers. The ones that you sent on your deathbed. You were still texting after you could not speak and managed to have Penny’s flowers delivered for my birthday.

“Let us make the most of the time we have left,” you had the florist write on the card. The flowers outlive you by a week.

The day after you died, struggling to write your obituary for the Jewish Exponent, I sit by your empty seat at the kitchen table with those cheerful yellow and white blossoms filling the stale indoor air with their sweet perfume. I cannot imagine reducing your beautiful life to a lifeless list of diplomas and titles.

Herbert E. Mandell, MD, November 12, 1949–January 19, 2016

Dr. Mandell served as Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association as well as President of the Regional Council of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and was Clinical Assistant Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Temple University School of Medicine. A graduate of Thomas Jefferson University School of Medicine and the Institute of the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia, Dr. Mandell worked evenings and weekends in private practice while concurrently holding Clinical and Medical Director positions at five area hospitals. He is survived by his wife, two adult children, and a brother.

This is not you. All I want, then and now, is to see the light in your eyes.

Suddenly, I yell, “Why are these goddamn flowers still here and you’re not?”

Sunday, January 21, 2018

My Dearest Love:

I want to open the box. I am curious what cremated bones look like. But I cannot bear to look at you in a Ziplock bag.

Eleven months after you died, I am still afraid to open the small wooden box filled with your ashes. Night after night your box stares at me from across the room as I lay on your side of the bed, hoping to catch a scent of you from your pillow. Finally, this morning I sit bolt upright and eye the box, swing my legs over the side of the bed, and tiptoe towards the bureau. I want to hold you.

I approach the box and open it. I lift the ten-pound bag of your remains and cup you tenderly against my heart. You feel and sound crunchy, like a bean bag.

“I forgive you,” I whisper to your ashes, “I forgive you for leaving me,” not realizing until I held you just then how furious I was that you died. But then I remember yelling at the flowers the day after you died.

I give your Ziplock bag one last tender caress and whisper a prayer of thanks for all that you were, all 162 pounds of you, once so much more than this. Gently placing your remains back in the box, closing the lid, I stroke the simple brass plate that bears your name.

Herbert Elliot Mandell. Nineteen letters. Ten pounds of ash. A paragraph for the newspaper. The one who, on his deathbed, sent flowers for my birthday.

Monday, January 22, 2018

My Dearest Love:

Within a year after you died, I’d given away or sold all your stuff. Your clothes (I kept the yellow sweater that I loved), barbells, pellet gun for scaring away the geese, forty-two neckties, Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, never opened Encyclopedia Britannica, and bicycle. But I still miss, like a phantom limb, your bright red Kipling backpack that traveled back and forth with you every day to your Abington Club workouts. Inside the backpack were a stick of Old Spice deodorant, a hairbrush full of your curly white hair, and clean underwear. When it was not on your back, it hung cheerfully on the metal handle of the casement window at the foot of the back staircase next to our kitchen door, always at the ready for the next workout and the next and the next, until too sick to breathe, let alone pedal a stationary bike, you stopped leaving the house. On Sunday, January 17, you said,

“Take me to the ER.”

You never came home. Still, I believed you might if the red backpack remained there. For months it hung from the window handle. At the ready. I knew what was inside without opening it. Preparing to move, even after I emptied our house around it, I was unable to touch, open, or move the red backpack. Each day it called to me as I walked by. “You know what you have to do,” it taunted. One night I grabbed the straps and hurled it into the trash can just outside the kitchen door, slamming down the lid. Trash night! And before I could change my mind, I sprinted up the driveway to the street dragging the can.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

My Dearest Love:

A bright, cold day exactly one year after your death, the kids and I met out back in the gazebo overlooking the pond, your happy place. I carried the Ziplock bag with your ashes and, using a stainless-steel coffee scoop, took the first spoonful and threw you over the side of the gazebo. A gust of wind came out of nowhere and pulled you up towards the sky. We watched the sun sparkling on your crystal filaments–angel dust, you. Then slowly the air grew still, and you landed in the frozen grass. Lydia formed you into the shape of a heart under the dogwood tree you planted by the pond. Dan poured you in a circle around the roots of the white pine tree he started as a tiny sprout in fifth grade, now taller than the house. We went to the grotto and Lydia sprinkled you inside that magical quartz cave you loved so much. Dan tossed you into the exact spot where you pulled him out of the pond when he fell in at age four. In the woods, he re-enacted his little boy’s fears of the dark along the wood chip path, walking in, walking out, walking back in a little further.

“Thank you, Dad, for taking away my fear, for making it safe,” he said between sobs.

I climbed into the fishing twine hammock above the dam, strung between two trees, and rocked there a bit, hugging you in your Ziplock bag, remembering the Nova Scotia fisherman we met, who tied all the knots by hand. I threw a scoop of you down the little waterfall towards the pond next door. Into the woods we scattered you amongst beloved buried pets whose graves you solemnly dug: Dusty the chinchilla, Mo the ferret, Henry Hannukah Hamster, countless bunnies. Dan took you to the perimeter of our property, demarcating the “fiefdom” you tended so carefully. Lydia led us out front and placed the last of your ashes right under the mailbox.

“This is your home,” she said, “you lived here.” She had the three of us hold hands by the pachysandra. We each had the fine white powder of your ashes covering our hands, clothing, and shoes, too.

“I have Dad all over me,” Lydia said looking down at her blue jeans, now chalky white.

As the kids and I walked slowly back into the house, I clung to them again, as I did during your funeral one year before. But this time I felt lighter.

How does it feel to be spread over two acres? And all over your wife and children?

Margaret S. Mandell is a 71-year-old widow born and educated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She attended the University of Pennsylvania from 1969-1977 where she met her husband, Herb, and pursued graduate studies in European History. Margaret served as Director of Admission for twenty years at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy in Philadelphia and after retirement trained to be a certified yoga instructor. A mother of two children, Margaret currently writes memoir and teaches yoga in Newtown, Pennsylvania, where she lives with the second love of her life, John.

Each letter is a snapshot of a moment in time. Exquisitely written. Heartbreakingly poignant.

There’s no way to improve on this. It’s perfect.

Love and miss you all…and my best to John.

Xxxxxx

Nancy

Nancy, thank you so much for reading this and for your kind wishes. Don’t be a stranger….Peggy

Thank you so much for reading Alligators to Ashes. How can I improve the reader’s experience?