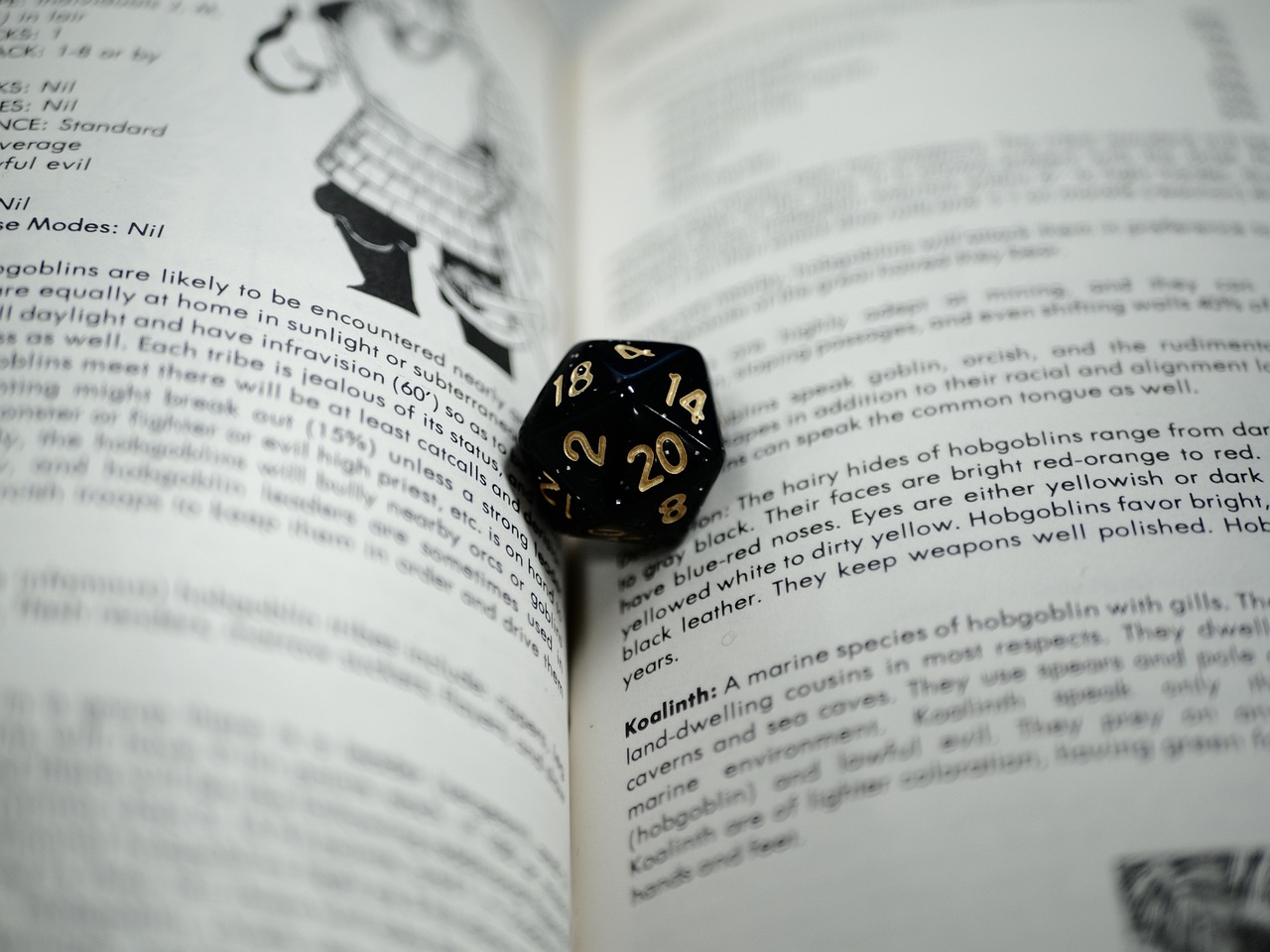

I started playing Dungeons and Dragons (DnD) about three years ago. I didn’t know much about the game and approached it as something new to do with my writer friends. By that time, we were tired of Cards Against Humanity and looking for something different. Luckily, one of my friends was an experienced DnD player/Dungeon Master and provided what we needed. I thought I could playtest one of my characters from my novel. Most of the time, I get to know my characters as I write, so this idea appealed to me greatly. I’d get to know Kayana and make better choices for her from the start of the story.

Boy, was I in for a surprise. Yes, DnD is a storytelling role play game, but it is also so much more. I quickly abandoned my idea of playtesting Kayana until I could figure out the rules and instead created Bacon Breakiron.

DnD was overwhelming at first, and me being me, I didn’t make it any easier. Experienced players often debate the best character for new players; fighter is considered easiest and spellcasters more difficult. I went straight for the magic.

I spent a good amount of time learning the mechanics of the game, but I was in good company. We faced giants and dragons and worked together to overcome any obstacle thrown our way. Our player group expanded (many of us writers), and I hosted DnD parties that included copious amounts of junk food and pizza. The story bonded us together in real life, bringing us together more often, and creating good memories. Before long, Bacon was a powerful hero and I created other great characters; Ront Rontsonront, Martin C. Bass, and too many others to list, all operating within the same story world.

What does this have to do with writing? And how did it help me if I couldn’t playtest my story character? Aside from real-life boredom busting and strengthening friendships, I found my writing changing in unexpected ways. I’d hoped to get to know Kayana like the back of my hand. Instead of learning about one specific character, I opened my eyes to the fundamentals of character creation. I learned about world building and pacing. Crafting an immersive story becomes a touch easier when you live in a story for hours at a time.

Worldbuilding: I learned the basics of what is important to know about a fictional world. As Bacon Breakiron, I didn’t want to know a hundred years of history or the intricacies of the local government right away. I wanted to know what impacted her directly; time of day, weather, terrain, types of creatures I might encounter, and if she wasn’t in a town, the location of the nearest one.

This doesn’t mean the hundred years of history isn’t important —if something in the past is still affecting Bacon’s world, then I want to know what happened, why, and how she should behave. For instance, if the land was conquered by a monstrous race a hundred years ago, I’d want to know so I can keep Bacon from being ambushed and killed. If Bacon is going to talk with a King, then I would want to know he finds the color red highly offensive and wearing a red dress would get her thrown into his dungeon.

The fictional world in DnD, or at least in our version, unfolds in a slow manner. Important information comes to light as it affects our characters. Not all at once or in a large information dump at the start of the game. I doubt any of us would sit through such a thing with pizza tempting us away.

This mirrors how an enjoyable novel unfolds for a reader. We get to know the story world as the main character moves through it. We see the immediate environment first and learn more about the world’s history or the political setting as it is needed. Too much information upfront might prompt the reader to set down the novel and move on to something else. Like pizza.

Fight Scenes: The novel I was working on at the time was a combination of old-style fighting (swords and arrows) and magic. I know very little about fighting and bought a fiction book with a lot of fighting in it to study the scenes as well as a how-to-write-fights book. I quizzed people around me who knew about self-defense and watched videos, but none of it helped me to think in tactical terms.

This is where DnD stepped in to help. Not only did I expand my knowledge of old-world weapons beyond ‘sword’ and ‘arrows’ to include mace, glaive, greataxe, crossbow, flail, and many others available to my characters, but I learned about the effectiveness of those weapons, their range, and how they are used in a battle. I also began to consider other aspects of a fight. Strength, dexterity, and constitution along with training, smart decisions, and knowing when to back down, all make a difference in how long a character can survive and how well they’ll do in a fight.

I also learned to respect a character’s limits. Bacon was a Cleric, which means she could do a combination of magic and physical combat, but she wasn’t super strong and was unable to take a lot of hard hits. Therefore, sending her to the front of the fight instead of staying back and using her magic meant she’d get knocked out and the other players would need to rescue her. As a new player, I sent her in anyway and ended up getting poor Bacon into all kinds of trouble (much to the frustration of the other players). Once I learned her limits and gained experience as a player, I practiced restraint and approached battle strategically.

This is a subtle thing when it comes to my writing of a fight scene. Instead of having my novel characters simply throw themselves at a bad guy and wing it, they try to come up with a plan. They consider the terrain and other threats that might appear during the battle. They take less risks; especially stupid ones unless they are suicidal.

Danger: Tying together both worldbuilding and fighting, DnD taught me to keep an eye out for dangerous situations. Awareness of Bacon’s setting saved me from pitfalls such as traps or quicksand as well as ambushes when she was out in the open. So now when I write, I think in terms of how a character might respond to their world. Traveling during medieval times? Then they might hire someone to protect them or keep a watch at night for thieves or bandits. My characters might need to know how to handle a horse or seek shelter in a storm. Those things may seem small, but in terms of story, they can be points of conflict or they can help make the world feel more realistic by adding in those potential dangers.

Character: Character development may be the first thing to come to mind when thinking about how DnD can help a writer. This was on the top of my list when I started playing. Indeed, the game does help with characters, but not in the way I expected. I thought by embodying a character I’d learn their emotions and thoughts, but DnD doesn’t require the players to delve deeply into their character’s soul to fight an owlbear. Instead, I learned more about dialogue and character voice.

Roleplaying doesn’t require accents, nor does it require that I change my voice (granted doing so helps bring a character to life). What ends up being more important is how I approach others, my choices, and how I say something (directly or indirectly, loudly or softly). Knowing my character well enough to speak as them meant I needed things like temperament, education, and background. Would my character understand words like prodigious? or use mouth breather for slang?

I played several different characters, and to make them feel like different people, I needed to adjust the way I spoke. Bacon, Cleric of Light, would get up early every day to meditate and greet the sun. She tried to save others when she could and had PTSD after battle. Bacon jokes to uplift others and speaks with a mid-range level of vocabulary. On the other hand, Ront was a barbarian who fought first and asked questions later, was coarse, and fell in ‘love’ with every person he met. Ront says his own name as a filler and grunts a lot with low level vocabulary.

A writer needs to make similar choices for their characters; however, they have a double-edged sword. Time. They gain the advantage of planning exactly what a character would say, but also the ability to overthink and make their dialogue sound wooden and unnatural. A gamer doesn’t have such a luxury, and while they won’t come up on an eloquent speech on the spot, they also can’t take all day to say something.

When I had to speak as Bacon or Ront, their voices came alive. I saw the reactions of others in real time and heard the cadence for myself. Reading a character’s dialogue after I’ve written it doesn’t carry the same weight. So now, I read dialogue aloud and think of phrasing and word choice. But I also try to take some pressure off myself. I don’ t need every utterance to be perfect.

Problem Solving: I can’t tell you how many times I’ve written myself into a corner, couldn’t think of a solution, then started deleting stories or chapters. Thinking outside of the box and finding unique solutions was not something I expected to gain from DnD, but that’s exactly what happened.

If Bacon is backed into a corner… swallowed by a T-rex or dumped in a vat of boiling oil, I have to think of something on the fly or she dies. DnD does not shy away from killing characters for making mistakes or bad choices so the threat is real. Working with other players opened my mind to new ways of thinking and changed the way I might approach a problem.

The shift in how I think and the regular practice of finding solutions quickly was enough to make me hold off on deleting scenes. I’m less willing to give up when an easy solution doesn’t present itself and I explore all angles of any given problem. Being more confident in my problem-solving skills makes me a better writer. I can raise the stakes in my stories and know that I will find a way forward. If I can’t find the way out, at the very least, I will make the outcome one that will satisfy readers. The ending will be earned because I’ve overturned every rock.

DnD can make storytelling fun and inspire a writer. The act of creating new characters and a new world with problems to overcome can spark new ideas or make old ones come alive and fuel a writer’s passion for storytelling. The parallels between writing a story and playing a game in DnD are unmistakable and give a writer practice in knowing what is entertaining and fun for a reader and what is not. The game gives writers a unique chance to cross to the other side and experience the story as a reader might while simultaneously creating a story.

Dnd has grown in popularity. It’s not just for nerds in a basement anymore; Stranger Things, Critical Role and several actors (Stephen Colbert, Joe Manganiello, and Felicia Day) have brought it to the mainstream. If you’re a writer looking for a fun way to improve your craft or gain some inspiration, give it a try without the fear of stigma. You might be surprised where the game takes you.