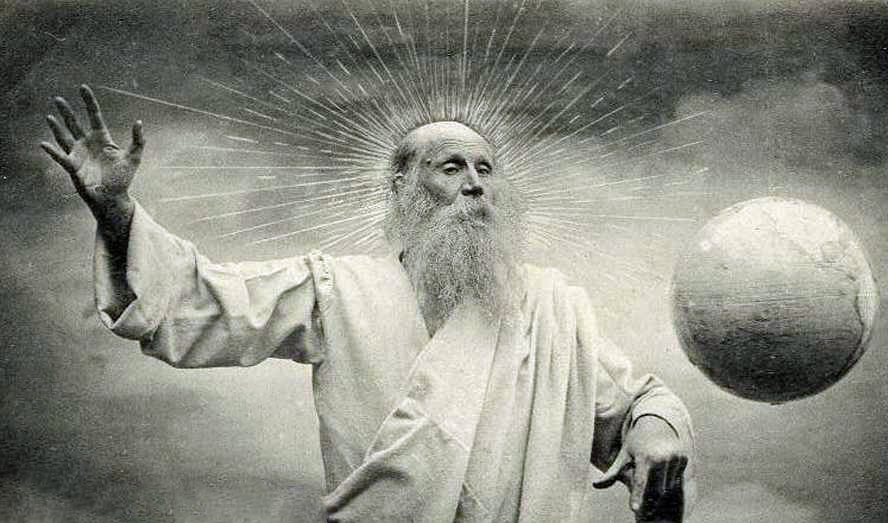

To be man means to reach toward being God.

Or, if you prefer, man fundamentally is the

desire to be God.

Jean-Paul Sartre

I am a prisoner, wrongfully condemned. The fact that they call me a patient is merely an exercise in semantics. A Public Health Officer is still a rat-catcher, after all. And I am a laboratory rat.

*

There are eight empty beds, and I am confined to Bed No. 9. Is my isolation a punishment or a privilege? The nurses (I have so far counted four – on six-hour shifts?) are bland, impersonal, interchangeable, always entering and leaving by the double-door at the furthest end of the otherwise deserted ward, walking (at least in the mornings and early afternoons) through the eight bars of sunlight cast by the tall windows between each bed, their neat white shoes clicking on the polished wooden floor. They remove the clipboard from the foot of my own bed, examine the chart it holds, make a new entry with a ballpoint pen, and reattach it to the tubular horizontal of an aluminum frame. Exactly fifteen minutes later they return with a glass of what looks and tastes like almond juice (or should that be milk, same as coconut?) and place it on the bedside cabinet between myself and (unoccupied) Bed No. 8. Then, after a professional, an economical, a briefly efficient glance of final appraisal, turn on the proverbial silver sixpence and walk down the vaulted, the sun-slanted, the starch-white corridor of my isolation ward, away.

*

“Why am I here?”

*

“Where is here?”

*

“Who am I here?”

*

I am dressed in a pair of linen trousers, as comfortable as pajamas but with pockets and belt loops – so not pajamas. No belt. A what they call in India a kurta: a sort of half-way buttoned man’s blouse, extending to the knees. The questions above are the questions I asked repeatedly of the nurses every day at every opportunity the first three days. On the fourth day I must have slept, for when I awoke there was a line of glasses of – almond juice? – lined up beneath my window on the bedside cabinet beside my bed; enough for twenty-four hours worth of six-hourly administrations. Also a hand-stitched, cardboard-covered exercise book and a 4B Faber-Castell pencil, my once-upon-a-time weapon of choice, sharpened needle-sharp, a tattoo needle, poison-green, as slenderly beautiful as an African snake. I tried to reach over, but I was terribly weak. Then I vomited all over my crisp white hospital pillow. And was only half-aware of being washed and having the linen changed.

*

Is this some kind of a trick? Will I condemn myself better / further if I write? I once wrote a review of Jacques Corrida’s Elephants Are Not Aubergines. We were pretty good friends, actually. We argued about everything, and were full of jealousy and hatred, but we always helped each other back to our homes, to our wives, our girlfriends, when we got stupid and argumentative and violent and drunk in Paris and Vienna and Amsterdam. Stretched now on a psychiatric bed, a prisoner not a patient, dearest Jacques, I lose words. Forget me. I walk into this annihilation of truth alone.

*

“The doctor will see you in his very due time. Doctor Jacobsen is very busy. He has also to deal with the Nietzsche Ward and the Kafka Ward. You are in the Sartre Ward. There are nine wards in total, these and six others. Are you mistreated?”

“No, but – .”

“Good. So may I assume our nurses are treating you kindly?”

“Well, yes, but – .”

“Superbly true. Doctor Jacobsen, in case you are unaware, is fluent in sixteen languages and has translated your poems into Dutch. He is an admirer of your work. In fact, he wishes you would write more. Hence the perfect exercise book and the perfect pencil. Incidentally, do you believe yourself to be God?”

“No.”

“No? Not at all?”

“Would God be chained to a bed in a psychiatric hospital?”

“That is a question better asked of God.”

*

I have started to have hallucinations; dreams that are not wholly dreams. Is there some kind of drug in these glasses of almond juice they keep bringing me? Peyote, perhaps? I am nearly certain that the majority of these visions occur when I am not asleep. After each one I meticulously record it in the exercise book provided. Was that its true purpose? Another question for the elusive Dr. Jacobsen. In the meantime, these are some randomly chosen entries:

I am standing on a white stage, totally white. White floor, white ceiling, three white walls. The auditorium is an enormous typewriter. The stalls, the dress circle and the audience; the chassis, the cylinder and the keys. Each ribbon spool is a private box.

Now I am alone on a circular silver-rimmed stool, facing the stage. On the left there is a paint-stained easel; on the right a Rolleiflex camera on a tripod, the slender telescopic legs of which are about five feet long. Between them centre-stage a naked woman sits on a canework chair, playing the balalaika and wearing a Chinese coolie hat. There is no sound from the balalaika.

The same (?) stage, but with the addition of a window painted on the white backdrop, a window with four panes, quartered blue and yellow, yellow and blue. On the left of the stage is a Punch and Judy kiosk selling cigarettes and magazines. On the right there is a man leaning against an old-fashioned black bicycle. The man wears a blue and white striped T-shirt and his face is painted in an oval of yellow. He is sharpening a pencil in the barrel of a revolver. The neat, conical, red-hemmed pencil shavings become the full size dresses of full-size flamenco dancers, executing tarantellas up the aisle of the auditorium between the rows of typewriter keys.

I am in some kind of art gallery or museum. Down the middle of the room there are glass cabinets, all of which are empty. On the walls, in elaborate picture frames, are sheets of what look like aluminum. I walk on into a second gallery, then a third, each more or less identical to the first. I become more and more confused and afraid. At the end of the third gallery, beside the entrance to the fourth, there is a man dressed in the uniform of a security guard, sitting on the platform of a step-ladder. He looks down at me and his face, only inches away from my own, is the papier-mache mask of a wizened old man with a hooked-nose, red cheeks, and a ghastly painted smile. Then I am standing in a much smaller room, painted entirely yellow, and containing an ironing board, a typewriter and a bicycle wheel.

*

“Doctor Jacobsen will see you at ten o’clock tomorrow morning. Doctor Jacobsen is a very busy man. You will therefore confine yourself to answering questions, not asking them. Many of our patients do not have a personal interview with Doctor Jacobsen for several weeks, even months, after they arrive. You have been with us only seven days. It is quite a privilege.”

“My pencil? My exercise book – ?”

“Will be returned to you in due course. It is essential that Doctor Jacobsen prepares himself thoroughly for your consultation. The doctor is a very meticulous man. You will understand everything when you meet him.”

“And afterwards, if our interview is satisfactory, will I be released?”

“Be discharged, you mean. Oh, for that you will have to ask Doctor Jacobsen.”

“But you said – .”

“I, too, have other patients to attend. In the meantime, our nurses will take care of you as before.”

And with that she (she being what – the Ward Matron?) turned abruptly and walked back through the long, empty, sun-sliced ward.

*

I am walking along a boulevard, a broad, tree-lined boulevard, beside an elderly man in a motorized wheelchair. He wears a black suit and a black Homberg and the hands on the arms of the chair are twisted, semi-paralysed, with arthritis. I realize suddenly that I am shirtless, naked to the waist. As we approach one of the regularly-spaced trees I see that it is covered with butterflies, of the size and brilliance one might associate with the tropics. I spread my arms, inviting them, and eight or nine flitter down and settle on my shoulders and chest. “Look,” I say to the man in the wheelchair beside me, “I am covered with butterflies!” He smiles a malicious smile. He says, “No, they are not butterflies, they are vampire bats. And they are drinking your blood!” I look down at the obscene black leathery wings, at my chest and the front of my white linen trousers soaked in red. I start to scream.

*

Notes towards a full report on Patient: Sartre / 09 by Dr. Isaac Jacobsen, Faculty Director, Antonin Artaud Institute, Prague, 12.15 pm, Thursday 26th June, 1947.

-

- Given the absence of other patients I conducted the consultation in the Sartre Ward itself. Patient: Sartre / 09 had been administered 15mg Hydrotechnochloroamylantonine precisely 45 minutes prior to consultation time.

- Using a technique pioneered by Dr. Adolf Kraken in Zurich (re. The Journal of Clinical Surrealism, Volume 24, No. 11, November, 1949) the patient had received small doses of synthetic peyote administered at six-hourly intervals over the preceding five days, and had furthermore been enabled to record the effects of the drug. It must be understood that the patient remained unaware that any form of drug was being administered.

- Apart from his insistence on referring to himself as a “prisoner,” the patient remained calm, lucid and amenable throughout.

- The entire interview was tape-recorded, with the patient’s knowledge and consent. A full transcript will be made available to senior members of the faculty within forty-eight hours of the interview’s having taken place.

- It will be the recommendation of myself, Dr. Isaac Jacobsen, Faculty Director, Antonin Artaud Institute, Prague, that Patient: Sartre / 09 be committed for an indefinite period, subject to annual review. It is furthermore put on record that, in my own personal and professional opinion, and if the patient responds to treatment, this term of committal should not exceed seventeen years.

*

A white room, totally white. White floor, white ceiling, four white walls. Nine tall and slender windows, eight of which divide nine elongated beds. White sheets, white uniforms, white hands invisible on white-faced clocks. White days, white nights, white dreams remembered white.

*

“Atheists are people who do not believe in God. Surrealists are people who believe that they themselves are God. One cannot consistently be both.”

“I am not a Surrealist. I am a reporter. I commit to paper nothing except that which I can see.”

“And if what you see does not exist?”

“It exists by virtue of my seeing it.”

“Perhaps. But I would prefer to suggest that it exists by virtue of your painting it or writing it down. Tell me: Would the universe exist if it were only in the mind of God?”

“It would exist. But only in the mind of God.”

“Well, let me put it another way. Do your dreams, your visions, whatever you care to call them, those which you have so eloquently recorded in the exercise book provided, do they have an existence independent of yourself?”

“Yes.”

“Let me be quite clear what I am asking. Would they have an independent existence if you did not write them down?”

“If they did not, they would not have an independent existence after being written down. Writing is not creating, it is recording. If you read what I have written, you have experienced what I have experienced, independently of my experiencing it.”

“But ultimately dependant on your having subjectively experienced it first.”

“Something can be objective even if it is only experienced by one person. Otherwise something experienced by twenty people would be exactly twice as objective as something experienced by ten, which is patently absurd.”

“But if you did not write down your dreams, they would have no existence outside yourself. That is the definition of subjectivity. If you wish to redefine the concept of subjectivity, then our little discussion here becomes merely a game of chess, moving semantics around on a hypothetical board.”

“I do not wish to change the definition of subjectivity. I wish to claim that subjectivity has the same empirical reality as objectivity.”

“You imply that art would exist if it did not exist?”

“I merely contend that art exists before it exists.”

“The logical conclusion of which is that all literature and painting is superfluous? I’m afraid you postulate a rather barren aesthetic. Even God is not too proud to share His vision with the rest of us.”

“Yes. But that vision would exist even if He chose not to share it. As art would exist even if it were not painted or written down. Art is created in the mind; it is merely recorded on paper.”

“But without such a record, how can it be known to exist?”

“Existence is not predicated on the knowledge of existence.”

“Are we not in danger of confusing epistemology with aesthetics?”

“I was not talking about aesthetics. Aesthetics is the philosophy of art. I was talking about art itself.”

(At this point the tape-recorder was switched off to allow Dr. Jacobsen and Sartre / 09 to drink some green tea. The first voice heard when the machine was switched back on was that of the patient)

“May I ask a question?”

“Of course. Please, go ahead.”

“But I was told – .”

“You were – ? Ah, yes. Frau Karloff. An excellent clinical assistant, but inclined to be a little, shall we say, rigid where hospital rules are concerned. Please.”

“Why am I in the Sartre Ward?”

“As I thought you fully understood, you are undergoing observation prior to treatment for Solipsistic Surrealism, a condition seriously complicated by a parallel tendency to Abstract Expressionism. It is serious, but by no means impossible to cure.”

“No. I mean, why the Sartre Ward? Why not the Kafka Ward or the Nietszche Ward?”

“My dear fellow, these are just the names we give to the wards. They bear no relation to the nature of the occupants’ condition. An innovation of my predecessor, Doctor Pretorius. So much more human, don’t you think, than Ward One, Ward Two, Ward Three…”

“Then why am I in solitary confinement?”

(Although not in the transcript, we can imagine that at this point Dr. Jacobsen recoiled slightly, such that the shaft of sunlight made his circular spectacles suddenly opaque. He said,)

“I think that is enough for today. Frau Karloff will be with you presently.”

(and walked, rather stiffly, through eight consecutive Japanese screens of rice-paper sunlight, past eight empty silently echoing beds, to where an out-of-focus hazy-white chess piece wearing a nurse’s uniform stood discretely to one side, motionless, emotionless, against the backdrop of the swinging double-door)

*

I dreamed last night. I dreamed last night of the Boulevard Raspail and of the assassination of Jacques Corrida.

There was snow on the ground and the roofs of Paris were black-wet with melted snow and silver-gray where they caught the light of a perfectly full moon. A few misshapen ochre-yellow windows gleamed dully out of the gray plaster walls. On the corner of the boulevard a single streetlamp; on top of the streetlamp a bowler hat. Then suddenly, sitting at a table with a typewriter in the snow in the middle of the street, was Jacques Corrida. His face was yellow in the yellow light of the lamp. Then appeared three figures without faces and dressed entirely in black leotards, holding cardboard swords and shields shaped like ironing boards. They were very thin and moved like spiders, and made no visible marks on the snow, which was anyway no longer real snow but broad swathes of white paint. They moved in on Corrida, who was typewriting furiously, the pages spooling out of his typewriter and spilling over the snow like the hem of a wedding dress, and raised their swords. Then one of them shouted but there was no sound and I looked up and in my own hand was a sword, the blade wrapped in silver foil, and the moon was a broken bicycle wheel, painted yellow against a purple sky.

*

A red and yellow room, yellow and red. Red floor, red ceiling, four yellow walls. An ironing board, a typewriter and a bicycle wheel.

*

The enemy of Art is the belief that dreams are subservient to reality.

Jacques Corrida

I paint things as I think them, not as I see them.

Pablo Picasso

I am a prisoner, wrongfully condemned.

Patient: Sartre / 09

Michael Paul Hogan is a poet, journalist and fiction writer whose work has appeared extensively in the USA, UK, India and China. His most recent collection of poetry, Chinese Bolero, with illustrations by the great contemporary painter Li Bin, was published in 2015. He is currently working on a book of short stories.