[842 words]

“For the dead are not dead” is a mantra infused throughout mythos— and repeated in a poem by Senegalese writer Birago Diop. It evokes images of Christ rising triumphantly from his tomb, of Osiris resurrecting after his dismemberment, of departed loved ones materializing in spectral form. It is also a paramount maxim in the graphic novel Zana. The concept of inexplicable appearances–where a departed soul lives again, where an alternate timeline is created– can be compared to an infamous arm-chair conspiracy theorist phenomenon: “The Mandela Effect,” where cultural events, people, or symbols are inaccurately recalled en masse. Though the first President of South Africa died in 2013, this has been vastly misremembered, with swaths of people convinced he passed in the 1980s, in prison.

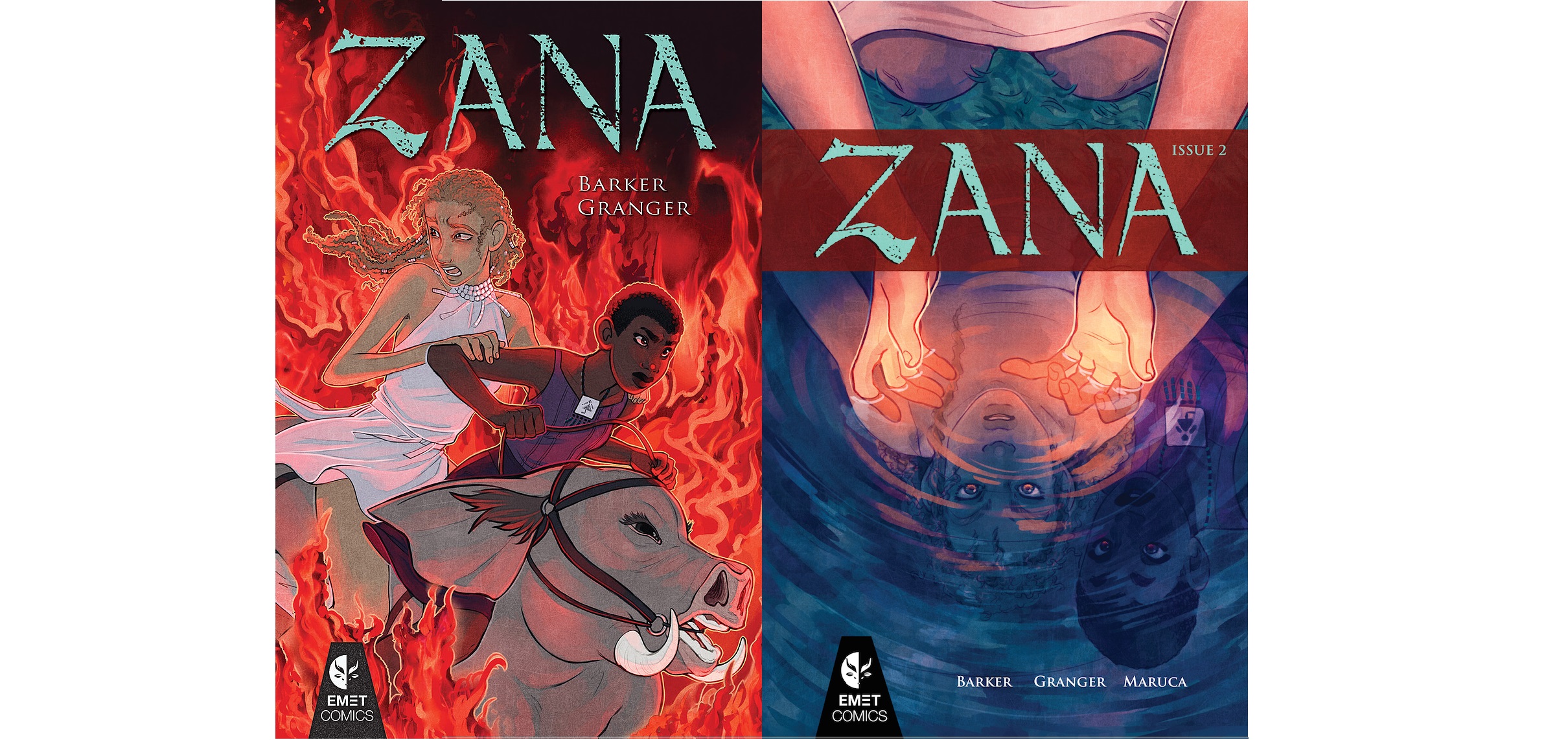

The first chapter of Zana was issued in 2015, and the entire five-chapter graphic novel was published in 2024. The first book in a series by Jean Barker, Joey Granger, and Luciana Maruca, Zana imagines an Afrofuturistic scenario set in 2048, where Nelson Mandela had died while imprisoned, never serving as President, and was executed for treason. A misremembering of African history is actualized, and the effects of a warped chronology are manifested: the entire continent finds itself in a racist apartheid.

The book’s protagonist and namesake, Zana, finds herself an adolescent amid division, categorized as an “Urban” (or mixed race) in a society segmented by labels. Districts are overseen by white “Royals” who carry out frequent cleanses to remove insurgents. In tribe area 237, where bucolic fields and space-age-style holograms coexist, it seems that inherent contradiction is woven into the cultural tapestry that envelops Zana. Granger and Maruca’s illustrations highlight this incongruity: the delicate, water-colored balminess of agrarian tradition juxtaposes the frigid manifestations of apartheid. A viridescent hill is rendered in delicate ink— a dainty patch of dandelions tucked into the corner—and below it, a grotesque pile of modern colonized architecture.

It is Zana’s sixteenth birthday, and she is a candidate for tribe initiation. She is called to undergo a ritual, conjuring a deceased ancestor to usher in her coming-of-age. Instead of taking her mother’s advice to contact her departed maternal Grandmother (or “Gogo”), Zana rebels and summons her unknown paternal Grandmother—a flame-adorned, infuriated white spirit who calls for Zana’s demise. “The dead are never gone; they are there in the thickening shadow,” echoes dauntingly as she materializes. Chaos ensues. Zana and her best friend Bisa escape tribal area 237 on the back of an elephant-horse hybrid.

Elements of Zana are startlingly contemporaneous despite being speculative and futuristic. Barker’s narrative rings prescient ten years from the graphic novel’s initial release. Notions of race, sexual orientation, consent, and bodily autonomy become painful pressure points throughout— Zana comes of age in a continuously regressive culture, where adolescence becomes intertwined with the weaponization of identity and individual expression. Zana’s rebellion against her mother’s initiation is a direct response to race-based taunting, her peers picking on her white paternal lineage. Her response of reckless decision-making first makes the reader shake their head in disapproval—and then relate to her desire to prove everyone wrong.

There is a refreshing power in Zana’s unrelenting teenage girl-ness. Considering the graphic novel’s emotionally hefty themes, Zana’s persona carries the reader through the narrative without feeling utterly hopeless in the grim alternate (yet prescient) reality portrayed. Instead of resigning to her situation and letting the oppressors win, Zana maintains a quintessential coming-of-age curiosity, determined to uncover the truth behind her paternal lineage. Zana is inquisitive in a culture that shrouds truth in secrecy, demonstrating the power of relentless inquiry amid fascism. She is concurrently stubborn and strong, simultaneously humorous and heroic. After arriving in colonized Grahamstown, Zana gawks at the local clothing styles in typical teenage fashion. In the next chapter, however, she stealthily infiltrates the royal class with the tactfulness of a secret agent. What is the adolescent experience if not a constant deluge of unexpected dualities?

Zana is consistently underestimated because she is young and female, an all-too-reminiscent patronization pattern woven throughout the plot. Even in the graphic novel’s chimerical setting of supernatural powers and materialized spirits, palpable sexism is deeply ingrained within Zana’s encounters. She is called a “pretty young girl” by a stranger on the path to Grahamstown and referred to as “princess” by an older man in a bar. Those who have experienced being a teenage girl feel a familiar pit form in their stomachs when reading Zana. One quickly realizes that the graphic novel’s narrative and message are not about fantasy or magical realism. It is a socially charged piece that crucially entwines pressing issues of misogyny and degradation within manifestations of the future—showing its devastating effect if mainstream culture continues on its current trajectory.

Zana’s plot walks a surprisingly fine line between the hypothetical and the pressingly tangible. It encourages the reader to speculate about how antiquated injustices can become intertwined with sci-fi, Tesla-esque ‘progress’—where seemingly bygone patterns of unfairness, like people, are never truly dead — erasing the boundary between past and future and centering readers in an unsettling present.

Purchase the 2024 omnibus version of Zana at Amazon.

Read our 2016 interview with Jean Barker.

Lena Bramsen (the reviewer) recently graduated from The New School with a degree in Creative Writing and was a member of the Writing and Democracy Honors Program. She explores the odd and nostalgic through words, digital art, and miniature dioramas—inspired by themes such as Americana, womanhood, and the eerie grandeur of haunted houses. Find her on Instagram @rococoraven.

Jean Barker (the author) is an Afro-positive South African former journalist with an anti-apartheid background turned feature filmmaker and graphic novelist. She began her professional journey in LA as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability (yes, that’s actually the name of a visa) and works between South Africa, Los Angeles, and San Diego, occasionally gigging as a film instructor and K-12 substitute teacher. She’s rewriting various feature and TV projects and seeking co-production partners for her second feature film.