[2539 words]

Camp Bucca, Iraq, 2003—

The tantal was there before we were. Mesopotamia was one of the earliest civilizations on Earth, so it was probably always there, waiting in the sand. At first, though, it mostly left us alone, watching to see what we were, I think. There were small things of course, like missing tent parts when we were setting up, tripping us on our way to the latrine, appearing as a camel spider the size of a plate to patter quickly across someone’s sleeping chest. But for the most part, we attributed those things to accidents or bad luck.

When operations were up and running—already with about a hundred detainees or so in a tent camp identical to ours, except for the concertina wire—I lazily poured sand into my millionth sandbag, each isolated movement becoming more and more absurd with repetition. Suddenly, the sand began to fill my lap; the bag, in my hand a second ago, was gone.

Ahmed, the prisoner closest to me, the prisoner always closest to me because he spoke English and made me laugh, said, “Ah, Tantal!”

I waited for an explanation, looking around for the bag.

“Not to worry. Tantal is a trickster. He pretended to be your sack!” We were sitting on the ground, wire between us, flies slapping our faces.

“It turns into things?” I asked. Even this early in the war, the air was murky and acrid with burn pit fumes. They came with us, from us, followed us around Iraq like smokey tails.

“Things, people, goats, anything.” He pulled his tan kerchief up over his face and leaned against his tent pole.

“But it doesn’t hurt you?” I said, handing him my water through the wire. The guards were notoriously slow to water everyone now that the prison was filling up.

He frowned. “Yes, sometimes he does. He will decide.” He finished drinking and passed the water back.

“Is this a kid story?”

“Hmm, like children? No, no. Tantal is real.”

U.S. Army Field Manual 3-19.40: Military Police Internment/Resettlement Operations, 2001

7-21. Sometimes, prisoners must be separated from the larger population for more intense custodial supervision.…. Prisoners may be placed in administrative segregation while awaiting the results of an investigation or for protective measures, medical reasons, or homosexual behavior.

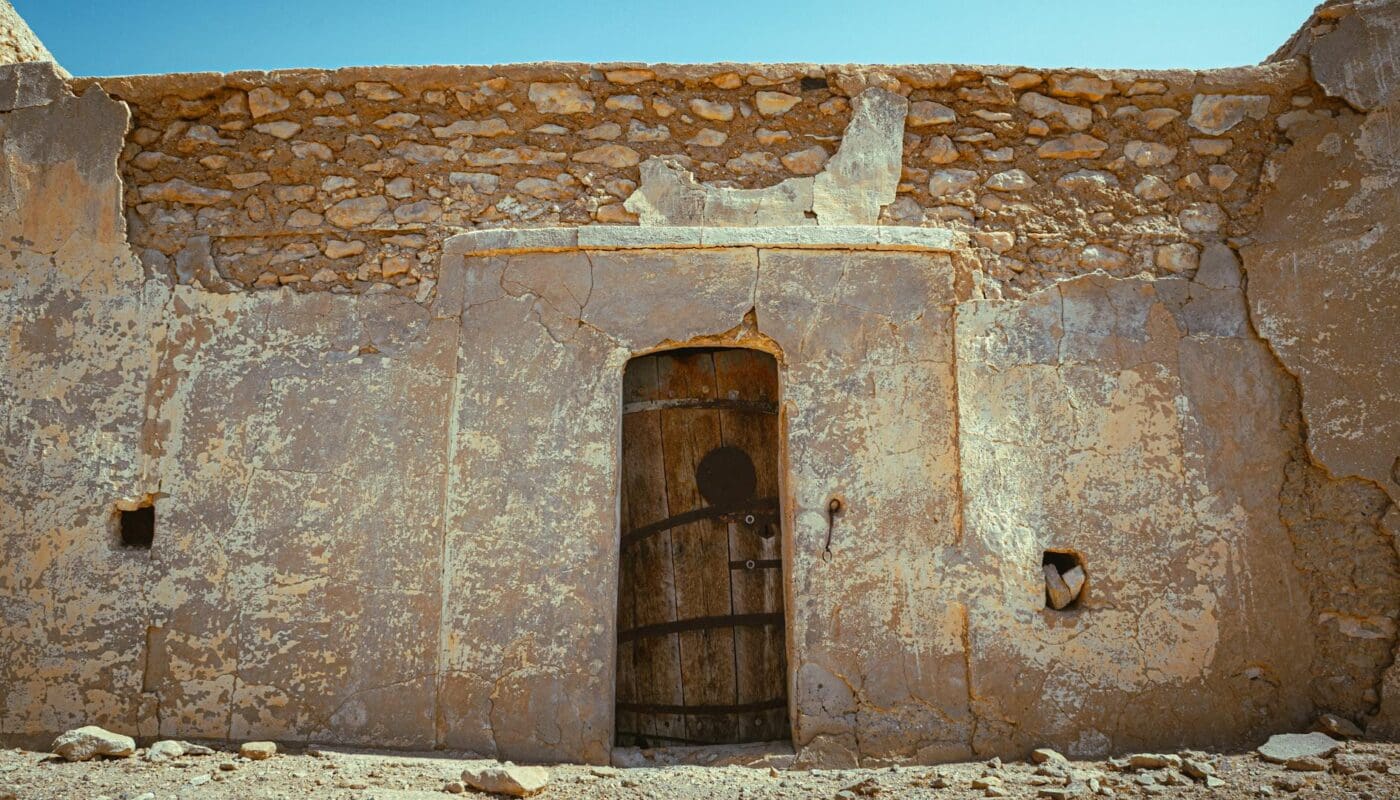

I did not find my sandbag, and I began to pay closer attention to any strange events in our camp. After the detainment perimeter was finished, I couldn’t see Ahmed much because my new mission was setting up the solitary cells that were outside the general population. The only structure in the sand when we arrived, it consisted of three walls. No roof. No door. Inside, were two cells on each side with bars like a real prison, if a real prison was open to the sky. Someone called it Iraq-a-Traz, and the name stuck. There was something about that place, some secret history in the walls and bars that gave it the strength to survive there, where nothing else did. Nothing for miles in any direction except the ruins of a tiny prison. Who was it built to hold? I wondered about it all the time, but inattentively like a song on loop in your brain. When the tantal showed up again, I decided it was meant to hold it.

The Arabic cell numbers were painted red, 1-4, and the tantal appeared in cell ٢. Always in two. It took the shape of a hedgehog, quietly digging around for food, a bit of red paint in its fur, like it had been there as long as the cell itself. I was nineteen and not particularly hard-working or social, so I spent a few days feeding it, trying to convince it that we were the good guys. It seemed more important to pacify a shapeshifter than to ready the cells for prisoners requiring solitude. I mean, they didn’t seem like real prisoners, just locals the MPs rounded up to interrogate.

Tantal was partial to lettuce, which we rarely had, but I did the best I could, and he would come right up to me when I went in the cell, always hungry. He never said anything, but I wasn’t crazy; he didn’t speak as a sandbag, either. So, I just talked to him about my family back in the States, a bird-ghost I’d seen as a kid that reminded me of him, and how we were sure to leave any day now so he could have the cell to himself again. And, yes, I was happy for the first time since being ripped from home and dumped in a sandbox. We had each other, and things seemed hopeful.

7-25. Disciplinary measures are imposed on prisoners to correct deviant behavior and to protect other prisoners, the staff, and government property. Abusive measures are not imposed… Prisoners are medically cleared before being placed in disciplinary segregation, which may not exceed 60 consecutive days.

But it couldn’t last. One morning, he wasn’t there when I walked in, and he didn’t come back the next day, either. I left as much produce as I could get there for him, but eventually I had to start working, so I couldn’t keep a close watch. Though, of course I took the time to visit Ahmed, to see if he knew where Tantal might wander.

“No, I don’t,” he said, peeling the label of his water bottle, his black hair falling over his eyes. It was getting longer. “How do you know this hedgehog is Tantal?”

“Oh, trust me. It’s him.”

Ahmed watched me thoughtfully. “I suppose he must go where you go, then.”

I couldn’t help smiling. “Yeah, I think you’re right,” I said.

Ahmed continued watching, not smiling back. “He has a dark side. You should be careful.”

I pretended to show concern, but I knew he’d never hurt me.

“Tantal will scare people to death. Destroy them.”

“Ahmed, I’ll be careful. But I think you’re wrong about him.” After all, Tantal wasn’t a monster. He was just a prisoner here, like Ahmed, like me. None of us could go home.

* * *

The night I’d finished preparing Iraq-a-Traz for its future occupants transferring from gen pop the next morning, Tantal visited my tent as fire. It was winter then, so each tent had a pot belly stove to warm it that we fed with propane, and he decided to send me a message through it. The flames started eating the tent wall near my cot, the closest to the stove. Hungry, beautiful little tongues licking the vinyl. I drifted, just for a second, and could see my sister’s bird again, could hear its short cry. It was the smoke it died of, when it couldn’t get out of its cage. Not the fire, but its ghost was always on fire for some reason.

Anway, Tantal didn’t mean any real harm. He knew I’d survived fire before and would put it out quickly—before the other soldiers even noticed, in fact. If he’d wanted to kill us, he would have chosen a more surefire way to do it, so I knew he was just upset about the little prison being used again or maybe only about his cell. Either way, I was relieved he was back.

EMERGENCIES. Confinement facilities provide custody and control of prisoners during emergencies (fires, escape attempts, and other disturbances)… Properly training custodial personnel and reviewing facilities and restraints can prevent or greatly reduce the possibility of escapes. Escapes result in emergency actions being executed and guards and prisoners taking immediate action according to the facility SOP.

I was careful to be discreet in the special attention I paid to Tantal when they put him into Cell Two. He looked unwashed and broken like the other three detainees that required isolation, which I expected, but I was surprised he didn’t choose a form that spoke English. It made it more difficult to decide what he wanted.

He spent a lot of the day smearing feces on the bars and muttering to himself. The guard who relieved me said he’d killed an old lady in the village near our camp. Of course, he was wrong about that because Tantal didn’t exist then. He was a hedgehog then. Still, the rest of his behavior was confusing, and I couldn’t help but miss his old form. Even fire had been better than this.

In the days that followed, though, I realized that I didn’t need him to tell me what he wanted. He could only want one thing: to be out of Cell Two. To be free. He began to slow down a bit and watch me more. It was obvious he was beginning to remember me and that we were friends. He stuck his hands through the bars to me when I came on shift, and I passed him whatever treat I could find. He was less interested in lettuce now, but he certainly loved meat, so I gave him what I could, except pork, of course. I got him a blanket, too, because it was still cold at night, and convinced the commander to allow a pot belly stove just on the coldest nights.

I was worried that the other three prisoners would notice my attention and become jealous, and they did notice. But while they stuck their hands out for food, as well, they didn’t seem to get agitated by my attention to Tantal. They all watched me silently when I was there, and when I left, I heard their resumed frantic, hushed conversation in Arabic. I knew Tantal was pacifying them for my sake, and I was grateful to have him.

Army Regulation 190–8: Enemy Prisoners of War, Retained Personnel, Civilian Internees and Other Detainees, 1997

3-6 (f) (2). Preventing escape. The camp commander will ensure that each EPW understands the meaning of the English word “halt.” If EPW attempt to escape, the guard will shout “halt” three times, thereafter the guard will use the least amount of force necessary to halt the EPW. If there is no other effective means of preventing escape, deadly force may be used.

The fire that killed the bird when I was a kid, killed other things, too. But the bird was the only thing that was alive. The rest was just stuff and ideas of who we could become. Different people with different futures. It was a winter without heat then, too. The fire was so warm, I remember. So bright and clean. No one ever asked how a house without electricity burned down. I suppose they assumed we’d started it to keep warm. Maybe my mom even said that. I don’t remember.

(a) In an attempted escape from a fenced enclosure, a prisoner will not be fired at unless he/she has cleared the outside fence and is making further effort to escape.

I was off duty the night the fire broke out in Tantal’s cell. Fog surrounded the chow tent where at least three other soldiers were eating. Record fog, the memorable kind that forced you to notice the other soldiers eating with you, so that later four people were sure about who was eating dinner when the alarm blared, when two of the prisoners in isolation took advantage of the smoke and fog to run when the guard unlocked the cells.

The smoke didn’t kill them, like it did the bird. Every breath they took from the day we arrived was full of smoke. Like training for that night, I thought. It was all just training.

(b) EPW attempting to escape outside a fenced enclosure will be fired on if they do not halt after the third command to halt.

I visited Ahmed not long after the fire. I guess I was lonely again, and the little prison was only ash and rubble now, nothing left for me to guard. He looked up with a new interest when I sat down outside his tent, the wire between us.

“Tantal is gone,” I said.

“I know. But if he ever comes back, tell him I need a favor.”

I looked over at him and passed him part of an MRE I’d taken for Tantal. He opened it up and noticed the beef was missing from the sandwich. “Such a trickster,” he said to me.

I smiled and ate my own MRE. When we were finished, Ahmed watched me for a while, quietly drinking his water, and then he said carefully, “Are you strong?” And he pointed to his head.

“I think so. Why?”

He considered and then said, “I think you should ask the woman guard what she found yesterday.”

I looked up, past the tents to the guard tower near the entrance. I could see Private Thomas eating lunch up there. I nodded, and he reached his hand through the wire and grabbed mine. “You are not alone. None of us. Come soon.”

He had never touched me before, and I started to worry about what Thomas might tell me she found.

(c) An EPW will have succeeded in escaping when he or she has: 1. Joined the armed forces of the power on which he or she depends or those of an ally of that power. 2. Left the territory under U.S. control or control of U.S. allied powers. 3. Joined a ship flying the flag of the power on which he or she depends, or of an ally of that power, in U.S. territorial waters, and the ship is not under U.S. control.

“Jesus,” Private Thomas said, when I entered the guard tower. “Two fires in two weeks, huh? You’re unlucky.”

I nodded.

“Apparently, they had it all worked out once the commander installed the stove. How stupid could he be? And one of the guys that got out was the Old Lady Killer, right?” she asked, shuddering.

I had a headache. It was so damn hot all the time. “I don’t know. Doesn’t sound right. But, uh, Ahmed said you found something? Yesterday, maybe?”

Her too-close eyebrows got closer, and she looked out across the compound. “The hedgehog?”

My heart started pounding. It was hard to breathe. “What?”

“Yeah, we found a dead hedgehog the other day. Is that what you mean? Ahmed—Seventeen Charlie Ahmed—I mean, saw it right outside the wire. All kinds of flies on it, spreading disease. I guess you don’t see a lot of animals here that aren’t goats, huh?”

“Can I see it?” I asked, steadying myself on the tower wall.

“What? No, you can’t see it. It’s gone, Sheffield. Incinerated.” She looked at me closely. “Why would you want to see it? It’s just a dead rodent.”

“Was there anything, I don’t know, weird or special about it?” I was going to puke.

“What the hell’s wrong with you? Was it your pet?”

“Yes, I think so.” Bile rose in my throat. I could taste it.

Her face relaxed. “I’m sorry. Yeah, actually. I think it had red paint on it. Is that what you mean? Hey, hey, it’s okay, shhhh, here sit down. Ooh, okay, yep; get it all out.”

Michelle R. Brady‘s fiction is included in Umbrella Factory Magazine, Hair Trigger Magazine, Ginosko Literary Journal, The Maudlin House, The Big Ugly Review, and Fine Lines Journal and has been awarded a Gold Circle Award for fiction from the CSPA. She holds a BFA in fiction writing and a JD. Find her at www.michellereneebrady.com. Follow her @BradyMichelleR.