The egg of flesh was placed on the table where my son and I were breakfasting.

“—Don’t,” I said, watching my son’s hand reach out to it. “Don’t touch it.”

“What is it?” he said.

Outside was bright, sunny and blue. Clouds wafted above, occasionally blotting the sun and giving shade. Down the mountaintop from my home were the other California villas, and at the bottom was the ocean side cliff. My son and I were on the patio alone, my wife having already left the table, and I was eating my typical breakfast—two hard-boiled eggs, a cup of black coffee—when one of my business intendants brought us a black box and unveiled the thing like it was a magic trick.

“It’s just what you see,” I said. “A blob of flesh.”

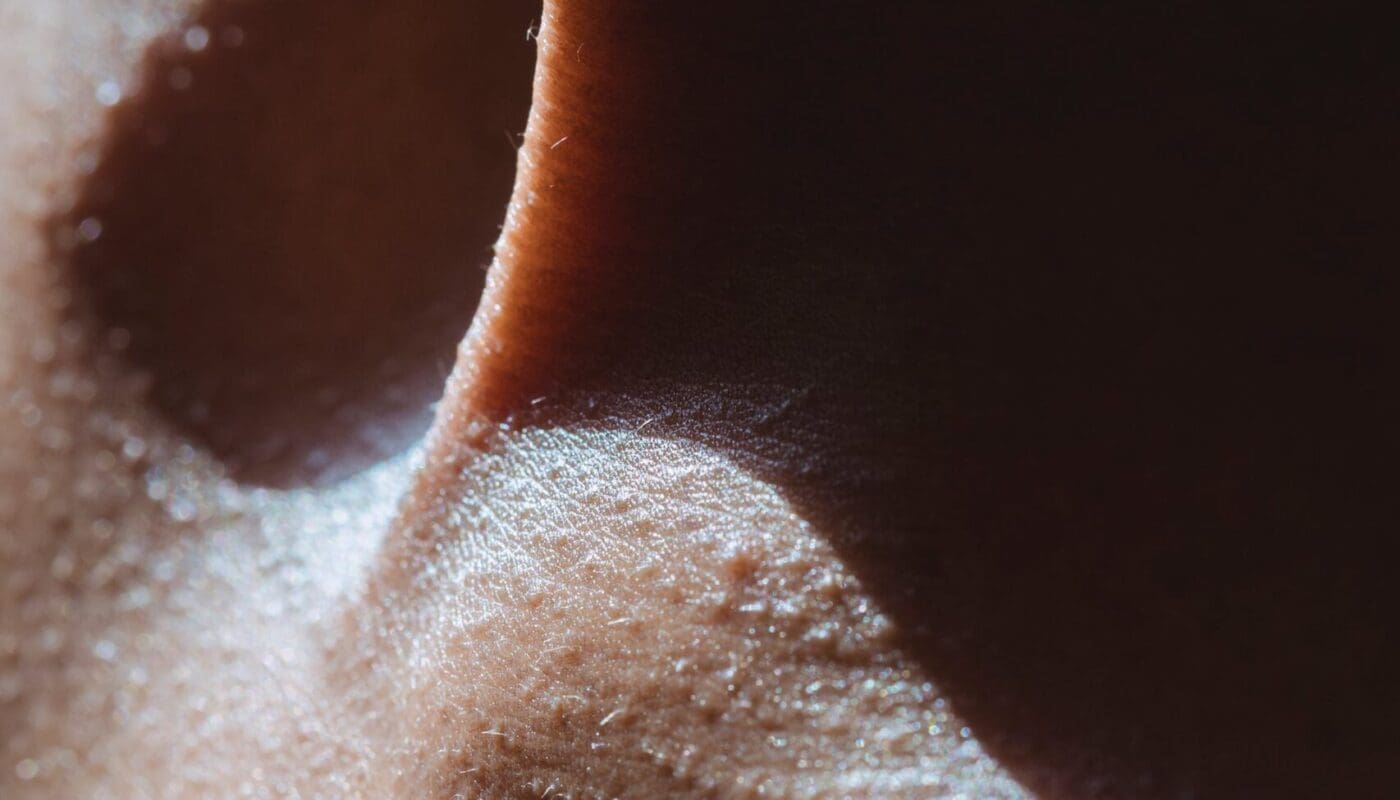

It was the shape of an ostrich egg, and slightly larger than one, too. Its ‘shell’ would bend to the touch, but it had skin like that of a human. It even had arrector pili—or goose bumps, for the non-scientific.

I picked it up.

“I have in my hands,” I said, “what I think is the very essence of hell.”

My young son looked at it. He didn’t flinch, but narrowed his eyes. “Why is that?”

I lifted it to my eye level. “See, this thing… it exists. Yet it has no perception. It can’t see, smell, think, feel, taste or touch, and yet it is all the same. It’s like you and me, perhaps, when we were fetuses in the womb. Except this one will never leave that stage, in a sense. It is right here, in my hands—but to it? It might as well be a million miles away. Prick it, it will bleed.” I shook my head. “But it won’t even know.”

“How do you know if it’s even alive?” he said.

“Oh I know. But the question is: does it know?”

Holding it aloft in my hand, I thought of the line from Hamlet when the prince held the jester’s skull: “Fellow of infinite jest,” he said, “… now abhorred.”

I turned the blob, a distinct bond coursing between it and myself.

It was from my laboratories. Velo-evo.

Velocitas. Evolution.

Captain of industry, they say. But I was a PhD in evolutionary biology before I left for business management.

“You get it, don’t you?” I said to my son, still standing outside. “It’s a byproduct. Of Velo-evo.”

You take simple, reproducing cells. Then you fast-engineer their growth—compressing a single year into less than minutes, even seconds—with stimulants, selective reproduction and genetic splicing. You put those fast cells in a contained and isolated chamber, and then you direct the course of their evolution through environmental controls, creating the life form of your desire.

The first was a bacteria that could quickly and easily produce clean water. I sold it to both developed and developing countries under a pricing scheme that required regular payments, then I spun out a separate investment arm with the proceeds to not only scale that operation but to, of course, create new ones. The next product was a type of supercharged pro-biotic. It rapidly restored the bacterial colonies inside the micro biome—that is, the gut—eliminating or alleviating all such associated illnesses: obesity, depression, autism. Even cancer.

“This is how the blob came about,” I told my son. The shade sail from the patio had been dispatched, and we were looking at it under cover from the sun. “It was an accident in the Velo-evo. An organism of cell reproduction that evolved, just for a moment, outside of our direct control. By the time we got to it, it was stymied and in this state.”

An intendant came around. He handed me a report.

“How does it live?” my son said.

“A process similar to photosynthesis, so I’m told,” I said, waving the report in my hands. “It’s all in here apparently.”

He looked at me, eyebrows contorted. Sitting in my chair, I leaned closer to him, the blob in my hand.

“You remember sculpting with clay that one time with mom, right?” I said. “What did you do with the leftover clay that you didn’t use on your sculpture?”

“Rolled it all into a ball.”

I smiled.

“Well, that’s what we have here. What’s left over from our creation has been rolled into a ball—what’s been thrown on the cutting room floor has, in a way, taken on a life of its own, eh?”

I put down the blob and reached out to him. My son.

I pet his head. I ruffled his hair. I kissed him, even.

“The day is coming. It’s here,” I said. “Time to find your mother.”

She was inside the glass walls of the home, standing at a table and looking over some documents of her own, a pair of gold bracelets jingling on her wrist as she set her hand on her hip.

“Have you seen him?” she said, meaning our son. Other intendants moved about on the enormous, expansive patio. Not just on the floor of my complex, but on the floors below, too.

“He’s outside,” I said. “Coming in. To take his lessons soon, I’d think.”

She beamed at me, but I nearly flinched, my mind so entrenched on the blob.

I made an effort to put my hand around her hip, landing it there for a moment.

She had told me once she hated me. My looks, to be clear. A nose too big, a face too wide. I was alabaster white with three large, jet black moles that slashed across my face: forehead, nose and jaw. Jolie laide, the French say. Someone attractive, but abnormally so.

“Ahh, the days are so long,” I said.

She kissed me on the cheek.

“They’re only that way to you,” she said. “I’ve never had a problem with it.”

I looked outside. The California earth was near red. Almost Martian.

An intendant named Sam came up.

“You requested these reports specifically,” he said.

“You’ve got them!”

I walked away from her to the patio, rifling through the papers and scanning the various titles the reports were given:

Pathologic Pathways After Detachment.

“Rhyming” Free-Floating States.

Right / Wrong in The Other Place.

—Ahh, yes.

My other enterprise.

The day was long. The sunlight hours were filled with many a “yay” and “nay” on the decisions that, like water cascading down stair steps, moved to the separate divisions of my businesses. But no work is as fun as a problem set before you, and so the day is meant for such menial industry, but nightfall is meant for our quests.

By evening, I was in my personal office on a cantilever overhang of the house encased in glass, facing the entrance, a desk before me. Both it and the office had photos and personal mementoes of family, old friends, and life events, and also those curios which invoked something: a marble globe, an impressionist painting of a spiral, a Giacommeti sculpture. And now this: a blob of flesh on a pedestal.

I had asked an intendant to put it there, to keep it separate but also keep it close. I wasn’t done with it yet. I wasn’t sure where it fit in with everything.

It moved as if it were a living egg shell, even though it didn’t know it was doing so. It thrashed about blindly on a plate, like an anesthetized tongue during a dental procedure.

The reports that Sam gave me earlier were splayed before me. They were written by trained clinicians accompanying—and at times smoothing out—the tumultuous emotional journeys of the patient-participants they observed. I was marking the reports with red pen, writing separate notes on a yellow legal pad, slowly forming my opinions. The one I currently read detailed a patient’s rising sense of unease:

“The patient busied themselves by rapidly caressing the fraying couch fabric while launching into an extended monologue, almost in an automata fashion, about—.”

The observer was trying to stay out of the experience as much as possible. He was only a comforting presence—so the subject wasn’t so alone as they underwent it.

“… I soon brought the subject a prized item of sentimental value,” the observer continued, “an old book with a lock of their grandmother’s hair, to ease their anxiety. This had no observable effect. The patient realized that the object could neither calm nor distract them from a growing despair.

A melancholia gripped the subject, but it was not to be treated or cured. It had to run its own course, like any medicine.

“At the 90th minute, the patient was presented the Rorschach panel of a ring-like object they were shown earlier. But this time, they asked that I keep the panel up, saying, ‘This one strikes me.’ They began asking it questions: ‘What have you known that I haven’t known before?’ and, ‘What assumptions are projections, vice versa, vice versa, and why are they dripping over my vision?’”

Who they were was suddenly melted down into a formless, prismatic and sentient ooze, and it poked, prodded and reeled from the image as if they were shown a stranger-filled mirror.

That’s when the patient in the report suddenly stopped. They dry heaved for a moment, then stopped again.

“The patient looked up. Their eyes saw something in the room not visible. They moaned in pleasure and pain. The patient had reached the critical juncture of the process. For several minutes their eyes had a far off look, as if blind—.”

—Blind, I thought.

Huh.

I looked at the blob. It had fallen sideways on the dish on the pedestal. I hoisted my feet on the desk. I remembered being blind once, back when I took this journey.

When I was Patient One.

It was years ago, before even my wife.

It was our seedling, psychedelic garage business—literally. Greg, flicking the syringe needle, tap-tap tapping my vein.

“Try this mix,” he said.

But I was ready.

“What we experience once inside is the real news,” ethnobotanist Terrence McKenna once wrote. “A nearby dimension—frightening, transformative, and beyond our powers to imagine. It must be explored in the usual way. We must send fearless experts, whatever that may come to mean, to explore and to report on what they find.”

Greg and I, together. He had calculated my body mass, the molecular mix of the injection down to the nanogram—my diet, even, and metabolism profile. I, meanwhile, had clocked my moods for months, managed my relations, duties and obligations, otherwise readying my brain. I fixed myself as if I were the galaxy’s solar equinox, in an alignment that foretold magic.

What came to pass was a lifetime compressed into a moment.

Transported, completely removed from this world, I found myself on a plain. The sky was an inky black and the horizon was a milky white, as if a colorless sun had just descended below the skyline. The two poles of reality—south and north, left and right, good and evil—had affixed themselves to one of two towers on the plain. One tower, emanating its message to my brain, affirmed that it was The Good, there since the beginning of Time, and the other—the other?—it also affirmed that it was The Good.

Moral relativism was toppled and buttressed, it seemed, by the same force—and I had no idea until then that (not only I) but all of humanity hung their orientation to life on that very dangling thread, when the space between the towers began to vibrate, and streaks of white star light weaved a fabric between the two towers, filling it with void-like white. The towers were not towers, but gate hinges. And it was opening, filling all the plain with an effervescent white, coming after me, overtaking my vision—.

The emptied needle was on a metallic tray by the nightstand beside me when I awoke. Greg sat opposite on the plaid couch in the garage, his jaw agape and looked into my eyes. He began taking out his notepad, hurriedly asking me questions.

But I could hardly keep to the task.

I gawked at the room around me. Nothing was different, but everything had changed. I had come into contact with a higher power. The world, this life, were not what they seemed—but instead both insignificant and precious. An adoration welled inside me and, before I knew it, I was yelling. I was crying. I was laughing. So much of my former life would now be gone; so much of a new life was now before me. “Friend, friend,” I said, feeling as if he didn’t understand me, as if he knew me no longer. “There is so much more to tell.”

No, everything was the same. It was me who had changed.

Back at my desk at home I sighed, leaving the old memory behind, and got up from my desk chair. I walked past the blob of flesh to the balcony, rubbing it as if it were an orb. It was night still, and the California hillside was aglow with the sterile, fluorescent whites of the other mountainside homes. I put my hands on the railing, smelling the night air.

Something about that ordeal made love come easy, and pain worth having. Something about it brightened everything; and both it and all else became hallowed. Sacred. Intensely new and beneficent. An idea was born that night, after I awoke next to Greg in the garage: to share what I had experienced with as many as I possibly could. And what better way, than through the corporation?

Behind me the elevator door dinged. It was Sam, my intendant.

“Sir, did you need something?” he asked.

“The status report. Of the clinics.”

He cleared his throat. “Well, ever since our lobbyist convinced Congress to permit our work to be administered in the clinical setting, we continue at a steady upward pace,” he said. “Now, the process is becoming as near-routine as an annual physical exam. Our small army of neuropharmacologists are happy. They’re mining a mountain of research. And every day a bastion of new, enlightened individuals walk back into this world a different and better person.

“Would you like the numbers?” he said. “The next batch of clinics are set to open in the Boston area. We just decided on their locations.”

“No, I don’t. I suppose not.”

“Looking for something in the research?” He motioned toward the stack of reports he gave me earlier.

Somewhere in the distance, I heard my son laughing. I looked into the dark, by the horizon, and thought of the towers I had seen. More real it was to me than what I saw in my backyard. I had been brimming with indescribable peace for months. But then the light flickered out, and what was an orb became just another rock. What do we not know that we don’t know? I glanced at the spiral framed on my wall; always moving forward, never moving at all.

It drove me insane with despair.

“I think so, yes,” I said. “That’s all. Thank you, Sam.”

He paused a moment, lingered—“You’re welcome, sir,” —and left.

I drummed my fingers on the railing, a gust of wind tossing the hair on my forehead, and looked down below at the black beach between the rock cliffs. I heard my name in the wind and looked down. There was my wife, calling after me.

“Hey there, you!” she said. “Can you see us alright?”

“Yes!—I think. Is that you?” I said.

“Yes! Come down here, see what your son is doing! It’s incredible.”

My son suddenly locked up, not to be made a spectacle. A dark form in the dim, white lights.

“Well, what was he doing dear? I can’t see it so well.”

“Oh, it’s hard to explain with all us yelling. Why don’t you come down and see?”

“For sure,” I said. “I’ll be right down. Let me finish what I’m working on.”

Her figure nodded in the half-light below. I turned and walked to another part of the balcony.

All marketing wants to trick consumers into believing their product holds spiritual well-being. Contentment and a positive affirmation, even, of a higher power. Me? I can deal it out in spades. But how come that glow never stuck? How come it left me?

I was lying down on the couch in my office, my eyes resting on the blob of flesh.

Greg, my first ally in that psychedelic garage business, guided me as I went back “down under” to learn more and map out this… this place. After the initial success, I was left only with asymmetrical discoveries unrelated to one another; a chimera-shaped map of interior exploration.

The last time, I was transmitted to a mountain summit. The peak of it—the size of a large bedroom—had been leveled flat, and there was a small, hand-woven shelter of twigs. The sky was mahogany red, mixed with apricot hues. Sitting in the shelter was a white-haired man who wore a worn-down suit of knightly armor. His eyes were baby blue and his look bore a patience tested beyond count. About us was winter and snow fell, landing only on the peak’s platform. I somehow mustered enough self-will to ask, “What is in the gate? Bring me behind the gate.”

He stepped aside, his woven-hut now opened to show homely, weather-worn cushions. “It is there, in the Lower Chamber, if you wish to see it.” He looked at me, a not unkind face. I stepped forward and he moved aside the pillows, revealing a square, black hole in the ground. “Do you wish to go?”

Slowly, I lowered myself through that narrow passage of all-consuming black. During that timeless descent, I could neither see, nor discern my thoughts but, by and by, a light came about me. And I fell into a small and simple bedroom bathed in a soft red light. There were no windows nor furnishings, but a bench was made into every wall of the room.

It was just this red room. And as I stayed there, pondering it, an odd and eerie feeling grew inside me, when I realized there was nothing outside. Nothing. Not even outer space was there, neither world nor universe—of all existence and matter, there was only this room that I was in. That’s a. Just this single room—when a small door opened.

Below was another room, smaller than a barrel, bathed in soft blue.

I crawled inside, curling to fit in, and waited to see what was behind the gate when the wall closed behind me, and the red room disappeared. I was stuck.

What came to pass in there was a moment that expanded to a lifetime.

I stood in my office, slightly lost my balance. Through the glass walls below was the home and complex, and I walked to the blob of flesh, running my hand over it again, letting my palm rest on it, feeling its soft murmurs and tremors—deaf to existence it was. The room was spinning; I dropped to my knees.

My stomach churned and I made to vomit, but nothing happened. I gripped the orb and held on, the room swinging and swinging and swinging. It stood over me; I held onto it.

Am I living? Or am I rock?

“Nothing can ever change,” I said. “Nothing can ever change, nothing can ever change.”

I thought I had mastered life; chameleon-like, color-changing life.

From outside, a child’s laughter could be heard, but soon it boiled over into tears. A woman called my name—louder, louder.

Louder.

Jason Ruiter is a Florida resident and former metropolitan journalist with bylines in the Washington Post, U.S. News and Politico. He is now chief of staff for a healthcare start up. He enjoys spending time with his fiancé, listening to Charlie Parker and playing the card game, Magic: The Gathering.