This month we’ve got a creative non-fiction piece from Mel, our editorial intern. Here’s what she’s got to say about it:

Nettle Fringed Earth was born of my attempt to complete NaNoWriMo last year. I set out to write a novel, but instead ended up writing about whatever inspired me. The image of nettles clustered around dark earth was one I couldn’t let go and the small spark grew into a project of sorts. I reflected on the time with my mother at Cathedral and what the park means to me, but I also researched the clear cutting of West Virginia, what the forest was like beforehand, and the history of my hometown of Aurora.

A couple of my stories are set there; Grey with WVU’s literary magazine and Treesong, here, with The Metaworker, but neither of them focused purely on the park. I suppose this piece could be called biographical in nature or perhaps creative nonfiction and is unlike what I typically write. Whatever label this story falls under, it is near and dear to my heart. With it I honor my roots and acknowledge where I am now. I never expected to share this story, but I am glad it found a place here at The Metaworker and I hope that you take some part of it with you.

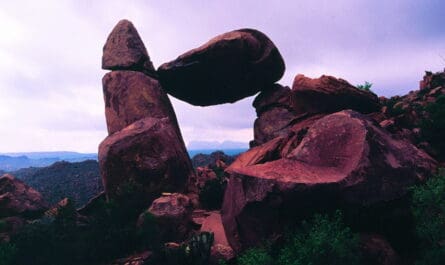

Cathedral State Park is the largest old-growth forest in West Virginia at 133 acres and contains the only uncut stand of hemlock trees in the whole state. Of West Virginia’s 15.3 million acres, 263 acres of uncut forest in the entire state remain. Let that sink in for a second.

Fifteen million acres clear cut.

Put yourself in those cleared fields. Don’t imagine sunshine and wildflowers. Instead picture one littered with discarded branches, leaves, and stumps. The bare earth bakes under the sun and shade loving plants, ferns, moss, lichen, wither and die. Fire sweeps through and burns away any tender shoots sent up from the stumps, finishing the job the lumberjacks did not. Smoke burns in lungs and makes eyes water. Rain brings relief from the heat, and wind clears away the smoke. It also causes the dark soil to erode, choking nearby streams. The brown water kills fish and amphibians. Without the trees to hold the water’s path, floods wash away anything left.

The field is silent. Nothing lives here.

And yet, there is one small place that missed the destruction. One hundred thirty-three acres. One acre is about the size of a football field. 133 football fields sound like a decent amount of land, but that doesn’t even make half a square mile. Cut in half by Route 50, the trails most tourists walk is closer to 60 acres. I didn’t need much more than a couple hours to walk the entirety of the trails when I was eight.

I played hide and seek amongst the giant hemlock trees, not knowing what they were or how special. I knew to avoid the stand of nettles that grew along the steep trail filled with tripping rocks because if I didn’t, I’d have a rash that stung and itched for an hour. I knew the rich dark earth there, fed by leaf fall, and the bridges with tiny fish underneath that would eat bread when I dropped it. The largest tree had a wood deck built around it because it was the biggest in the state. Deer roamed free, and sometimes a bear or two could be spotted. But I didn’t know the sadness, didn’t know that a scant few generations before me had so little regard for the beauty and magic the woods can hold.

My mom instilled in me a love of silence, taught me to take a moment to appreciate the fresh air there, and told me stories about how Cathedral came to be. Brookside owned what is now Cathedral and used to be a place where people from big cities came to partake of the cool mountain air and healing waters. It was owned by a headstrong widow who wouldn’t allow logging on the land and would only sell to the state with the stipulation that the trees must never be cut. Though, history remembers it differently. Branson Haas sold the tract of land in 1922, and Cathedral become a park in 1966.

Amazing how I could love a place but know so little about it.

The Old Stone Tavern had a pond and was a place I should not go. The bordering farm had sheep and a big red barn and boys on fourwheelers… a wild place of a different kind and to be avoided. A photographer came to the park and took pictures of the small streams that I dipped my toes in. Those photos were semi-famous and ended up winning some award. Some well-known artist came and stacked rocks in the streams and took more pictures. West Virginia University students come to study the trees and the hundred-seventy different species of plants. All visitors to a place I claimed as my backyard.

But of all the things I know about the place, what stays with me the most is the time spent walking the trails with my mom. The picnic lunches we took to the bridges. The family reunions. Swinging on the old rusty swing set with my cousin, competing to see who could go the highest, who could touch a branch with our toes before swooping back down again. Church services held in one of the old pavilions. And the snow that stopped traffic on Route 50 and brought a quiet so profound that mom would stop her stories just to listen.

Funny. I am still in that park. I’m not sure I ever left.

Yet I did. I lived in Lexington, Kentucky and Charleston and Morgantown. I don’t fit anymore. I’m cityfied now. But when I think of that dark earth, damp with rain or melting snow, I envision it with a ring of nettles—green leaves with saw-toothed edges dripping poison—protecting it. Outsiders only care about what they can take. I want that bit of virgin earth to be undisturbed, so it’s nice to think that if someone is going to take from it, they have to pay a price first. Even if that someone is me.

Image Credit – Pixabay License. Free for commercial use, No attribution required.