In the Third Year of great burning, Mo Mo, the Golden Emperor, made a journey to the monastery in which, as a boy, he had studied the arts of war and the teachings of the Tao. Mo Mo’s instructor in those days was a small, dark woman with delicate inscrutable movements, too yin for the youthful Mo Mo, who thought only to emulate the powerful thrusts and strikes of legendary warriors. Mo Mo hoped that his teacher still lived, though older and now surely even smaller, for he wished to tell her that he had learned that there is strength in softness, that he had been foolish in his youth and now wished to acknowledge her wisdom.

Mo Mo had long felt this obligation, but his years as emperor had been taken up by many battles, and his days burdened by the weight of governance, and he felt that his time was not his own to dispose of. But then one morning, when fifty winters had passed since his coming of age and fifty summers since he had left his teacher, it was heard that there were students who would return to the monastery where their master taught, to honor her, to share memories and renew acquaintance, and compare to see who had put their master’s teachings to best use in the world.

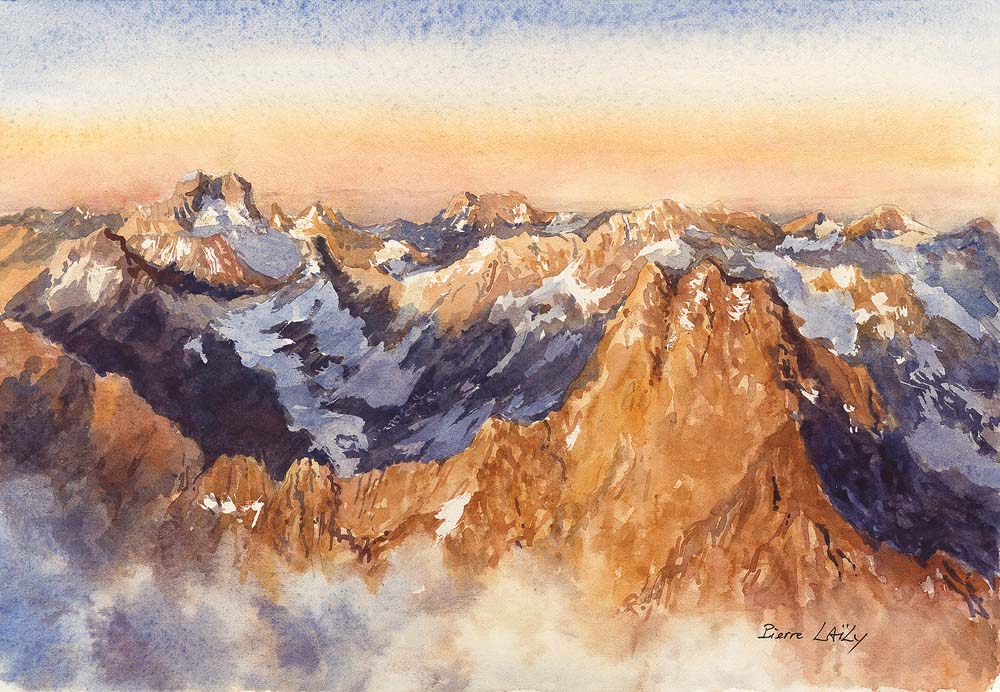

The emperor Mo Mo determined to be one in this company, and so he set out to cross the Shrouded Mountains and the Five Rivers, traveling alone, riding his fastest steed and carrying only a silken bundle and many memories.

Passing through villages and towns along the way, he heard tales and rumors of his fellows who were journeying to the reunion. One had become a great sage, renowned for his writings and beloved by his many students. Another had chosen to take up the law, and had become a fearsome contender in the highest courts of his province, a scourge of corrupt officials and an advocate for the pitiable and poor. And one scholar had transported himself into the body of a woman – a mystical feat that had never been contemplated in the days of Mo Mo’s youth.

Hearing of these marvels, Mo Mo felt himself measured and found wanting. He was emperor, of that there was no question, but on the other hand, his empire was not, in fact, all that extensive. He held sway over all the lands from the Shrouded Mountains to the Hooded Hills, but his fastest couriers could span that compact valley in two days. And while Mo Mo had ruled wisely, as wisely as he could, still there had been years of middling crops, there were beggars, and there had been typhoons that caused great destruction, which the unlettered people attributed to acts of the gods, but yet Mo Mo felt that he should have foreseen and made better preparations. In fact, his reign seemed to him less a record of triumph than a succession of lesser and greater emergencies that he no sooner dealt with than another came to command his attention.

And always, there were skirmishes with those outside his borders who sought to claim territory for themselves, and challengers within who sought to weaken Mo Mo’s authority through subterfuge or lies, or simply through the lawful claims of their rightful interests, for Mo Mo wished to be a just ruler, and he could not summarily dismiss such petitions. And so each day, through acts of mercy and justice, through battle, through inattention and weariness, Mo Mo’s empire was diminished.

It occurred to Mo Mo that his life might have been more satisfying as a scholar – to remain a student all his days, studying the texts, contemplating the Tao and discerning the secret meanings of all the warrior movements. Carry Tiger to Mountain would then be clear to him, whereas now he could only guess at what such a phrase might mean, and feel shame at his own ignorance.

And Mo Mo wondered whether perhaps another student, someone like his rival Ko Lin, might have ruled more effectively.

Ko Lin, at least, looked the part. When Mo Mo had last seen him, at an imperial function many years previous, ambassador Ko Lin wore simple robes that accentuated his height, in colors that complemented his jacket and shoes. And seeing this, Mo Mo regretted his own gaudy and mismatched raiment – willfully chosen against the advice of his own steward – and knew Ko Lin to be fluent in fashion, a language that Mo Mo disdained as mere vanity, but secretly sought to master, and failed.

Such were Mo Mo’s thoughts, prideful and rueful by turns, as he rode through the mountains.

After many days of travel, Mo Mo arrived at his birth village. The air was hot and wet, and his clothes hung limply. He wished to bathe and dress before he encountered anyone he knew. But no sooner had he found his way to an inn, when he was accosted by a stranger who called him by name.

“Mo Mo? Is it you? Oh, what a miracle. You are no different than the day we parted from school. You have no lines on your face! How is it possible?”

Mo Mo knew this to be a lie, for that very morning he had washed in a stream by his camp and beheld his reflection in a still pool. And he, too, had wondered at his appearance, for in his reckoning he was totally transformed and unrecognizable to himself.

But surely this was equally true of the stranger, for although Mo Mo racked his memory he could find nothing of the man who stood before him, short and bent, dressed in drab clothes dulled by long wear in the sun and worn through at the cuffs and elbows.

“I am pleased to see, you,” Mo Mo said, attempting to prolong the conversation without betraying that he could not remember his interlocutor. “Are you here for the gathering?”

“Of course, Mo Mo. But, you don’t remember me, do you?” he said, slyly. Mo Mo shook his head, with a gesture that denied the accusation while also expressing his regret at his own failing. “But of course, you don’t. I have changed so much, while you, the years have not touched.” Mo Mo smiled and opened his hands – ‘not so. Thanks?’

“It’s me, Ko Lin. Surely you recognize me?” and with that, Mo Mo’s vision seemed to clear and the picture before him came into focus.

“Yes. Yes, it is you, my friend,” said Mo Mo. “How wonderful to see you after all these years.” Mo Mo marveled at how Ko Lin appeared to be two people at the same time – the tall and envied diplomat he had known so many years ago, and the disreputable and shrunken old man before him. There was a hole in Ko Lin’s left slipper, and Mo Mo was shocked to see a long toe protruding, with a discolored yellow nail.

“But wait till you see who is here,” Ko Lin said, uncaring, or oblivious to the slovenly disregard of his robes. “Everyone! Nu Berg, Kah Ren, Val! I just saw Shih Su. She asked if you were coming, but I didn’t know what to tell her. She will be so excited to see you!”

Each name brought a vivid picture to Mo Mo’s mind. But Shih Su’s image was clear in a way that the others were not – sixteen, slim with dark hair and eyes, in a white and gold silk fighting suit. Of her Mo Mo had thought many times, always with regret and a cold and bitter self-recrimination.

Then Ko Lin pointed over Mo Mo’s shoulder and spoke excitedly, almost yelling in Mo Mo’s ear. “But here she is!”

Mo Mo’s breath ceased, and a brilliant wind blew across his face and filled his eyes, and he blinked rapidly as he turned…

But Shih Su was gone. Ko Lin was gone. Mo Mo sat up and rubbed his eyes, smoke-filled from his fire as he lay by the mouth of a cave.

Mo Mo gathered his pack and rode on in darkness, and wondered at his dream and how curious it was that an emperor whose every whim was law could not command his own thoughts. How should that be?

Mo Mo sought to think of something other than Shih Su, and he returned to the riddle of the tiger and the mountain. “Carry Tiger to Mountain,” his master calls out the name as she spins on one heel, sinking low and extended her arms, raised as though filled with a heavy burden. But a tiger? Mo Mo wonders. Who would carry a tiger? And why? Is the tiger tired? And what is in the mountain?

It is Mo Mo who is on the mountain now. And Mo Mo put aside his reverie and scanned the horizon before him and behind, for in these mountains there were indeed tigers, and it would be well for Mo Mo to loose his sword and be on his guard, and he slowed his pony’s gait, for Mo Mo could not see well in the dim light.

The path continued to wind higher, becoming rocky and narrow, Mo Mo reined in his pony and leapt down, but doing so he winces with pain in his hips. It occurs to Mo Mo that if he must ride, that it would be good to get down and walk every hour or so, and perhaps bend his knees and crouch or lunge from side to side to open the joints of his hips, for on this journey he had been so sore at the end of the day that sleep had often been impossible, tired though he might be.

Nodding to himself at the wisdom of this resolution, he looks up the path and behold, there is a tiger coming toward him, a massive beast, yet so silent that Mo Mo, whose hearing, it is true, is not what it was, had been taken unawares. Yet Mo Mo is not surprised. He has expected this, and perhaps, even looked forward to the test.

Taking a wide stance, he extends his sword arm, but, feeling a twinge, lets the sword fall to his side, and precious moments go by as Mo Mo rolls his shoulders up and back until he can raise his arm without pain. His neck is stiff, and so Mo Mo must turn his whole body to face the tiger now racing toward him. But Mo Mo knows what to do. He bends his knees to make a daring leap, a move that he had practiced many times at the monastery, where fifty years ago, Mo Mo remembers, he had leapt higher than any other student, and had been the only one to successfully master the technique known as Strike with Falling Fist. Mo Mo gathers himself to soar over the powerful beast, but realizes, too late, that his memories have distracted and confused him, his reflexes have failed him and he has been too slow, too slow. The tiger is upon him, reaching out with a paw like a fur-covered anvil to bat Mo Mo onto his back.

But Mo Mo rolls over with a sudden influx of renewed strength, comes to his feet and now makes his mighty leap into the air. But at the last moment, his left knee turns to water and instead of flying over the tiger’s head, Mo Mo stumbles and falls into its fierce embrace. The great cat holds him down with one iron paw, his weight a mountain on Mo Mo’s chest. With its other paw, the tiger casually pulls at Mo Mo’s sleeve, tearing his arm from his socket, then bends his head to sink daggerlike teeth deep into Mo Mo’s thigh. Mo Mo feels an agonizing pain, but also, spreading outward from his wounds, a great release through all his grudging joints that will no more have to bear his weight, as though his bones had all at once been changed from rusted iron to gold.

The tiger raises his head to examine Mo Mo, flesh and sinews hanging from its teeth, and seemed to judge that this meat is too old, too stringy, not to his taste and not worth carrying back into the mountains. And the tiger turned and walked away, treading on Mo Mo’s sword as he goes and breaking it into shards.

Mo Mo lay on his back. His pony stood nearby and dark clouds scudded overhead. Mo Mo lifted one arm. The tiger had been a dream, perhaps. Or he dreamt now, as he lay dying.

Or, perhaps, it seemed to Mo Mo, he was still a child, who dreamed that he had been an emperor.

The teaching of the Tao is not the Tao.

The study of the Tao is not the Tao.

Yet the Tao is all that is, and is not.

MORT MILDER Writer; editor; playwright; co-curator, Rough & Ready Productions NYC. Beginning instructor, Taoist Tai Chi Society. Born, St. Louis, MO. Resident NYC. mmilder@gmail.com @mmilder