There’s no getting around the fact that this has been a very unusual month. Here in the States, we’re facing the first impacts of COVID-19, and I’m not going to lie, it’s made my art and creation facilities shut down a little. So, for this newsletter piece, I don’t have much for you. What I do have is the beginning of a short story that turned into the beginning of a novella that turned into the beginning of a novel, and I’d like to share that with you all today. Disclaimer, of course, that this is a rough work in progress, and by no means polished or perfect (or even edited, really). Regardless, I hope it takes your mind off things for a little, and that you enjoy it.

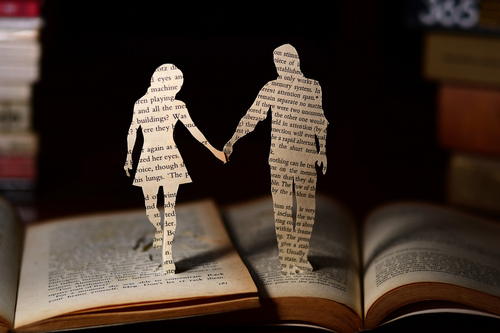

We could begin the story with once upon a time, but it would not be true. It is a story that has happened for every time, one that is past and one that we live now and we will find in years to come that the story was our future. The story is always happening. There is nothing once about it. How do you recognize a story that you’ve always carried? When does the story end and when does it begin and at what point is it just a part of you, as woven into your skin as the lines on your palm and the scars on your back and the callouses on your feet?

Remember this. Remember what they got wrong: Love was the first story we ever told. All stories are the same story. All stories are love stories if you look at them the right way.

What the storyteller means to say is: There is a man on the moon. He is there on purpose. Some stories have been here so long that they seem like they are not stories, just truths. But there is a story about the man on the moon.

We will leave the ghosts on your back where they are, for now. The storyteller must begin with a story. She will come back to you later, dear reader, because you are also the story. The storyteller saw you long before she ever met you, and she has been waiting for your story to merge with the one she is telling.

You asked for a story. This is what the storyteller will give you.

The man on the moon did not always have such a grand title. In the beginning, he was just a man. In the beginning, there was no moon—not the way you know her now, at least.

In the beginning, there was just a well, and the village that tended to it.

There were very few rules about the well, but they were strict. Firstly, the villagers were only permitted to fetch water from the well during the daytime. Secondly, the well must be sealed, airtight, once the sun began to set.

It was no easy feat to reach the well, so the villagers would rotate the task of sealing it amongst themselves. For centuries, one villager would make the journey to the well as the sun sank in the sky, and they would return by the light of a solitary lantern. Often, the villager would bring back one last pail of water. The journey back to the village was an arduous one, and far too many times the howling wind would snuff out the light of a villager’s lantern, and they would never be seen again.

There was a myth about this, of course—the village was small, and filled with unkempt rumors. The landlady at the local pub always told travelers that the missing villagers were sacrificed, that the wind was in cahoots with the well, and brought it human flesh to appease its hunger. She would say, if you looked closely at the water after a villager went missing, you could see that it was tinged a pale pink; the blood of its victim. She would say, right as a traveler took a sip of their drink, that the water of sacrifice always made for a better ale, and she would smirk as they choked on their beers.

This was all heresy, of course. Wells don’t eat people.

It was also said that the well made men mad—a rumor that had little considered all of the non-men who had gone missing over the years. Still, it was said that this madness would grip the bodies of the villagers, make their eyes roll into their heads and make their feet carry them back to the well. Once there, the madness would make men blindly throw themselves in, their bodies breaking and bending all the way to their watery graves. If the jump down the well didn’t kill them, it was said, the water would.

Nonsense and rumors, all of it. No bodies had ever been found at the bottom of the well, though it was too dark to see the bottom as such.

The water would conveniently turn pinkish whenever someone went missing, though.

There was one conjecture in the village that held weight.

The villagers, for all their chattiness, would not discuss one crucial facet of the well amongst themselves. It was an open secret, one that each villager would discover for themselves when they took their first shift at the age of eighteen (a third rule that the villagers had quietly stuck to when a child went missing on a well-sealing shift ages and ages ago). They did not talk about it, for fear of what talking about it might mean.

Children would often ask questions about the well as they grew older: why does only one person seal it? Why do people sometimes go missing? Why do we even seal the well?

The villagers knew the answer, but the questions were always met with the same response: “It’s just the rules.” Something in the tone of the adult’s voices ensured that the children did not press further questions, or discuss it amongst themselves.

The conjecture, then, that had any merit was one held by the vicar. He did not share his thoughts with any other villagers, but if one were to find themselves having a conversation about such things with the vicar present, one could parse the thoughts of the man and reassemble them in a nearly correct order.

The vicar believed this: the well called to certain people. Those certain people were not missing—they knew exactly where they were, and they made a choice to never return to the village.

It was not entirely the truth. It was not wholly wrong, either.

Thanks for reading, and if you can, keep making art. Indulge in it if you’re able to. Share it if you want to. Even the small fragments and WIPs matter. In the end, I think art is what matters, and I hope in the coming days and weeks and months, you’re able to find some art that gets you through.