We’ve been running The Metaworker for a while, when life doesn’t get in the way. I’ve also been writing something almost the entire time we’ve been posting. Not any one thing, but various things. I don’t expect anyone to realize that. There’s been no clear outside indication of it. Intermittently, I’ll submit my work for publication a dozen or so times before I wonder what I’m doing. And wonder if the whole thing is a waste of time.

This is ironic given the platform I’m writing this on.

To be clear: I respect the people who submit to us immensely, even though we have to say no to so many of them. If you aren’t a writer, (though if you’re reading this, you probably are) imagine all the toil of the 21st century job application process. But your life doesn’t really change if you’re successful. You might get a few hundred dollars if it’s a paying publication. You might also be able to put an imaginary pin on your jacket: published.

The Problem:

Is this all a side-gig?

That’s what I ask myself as I ponder that the core problem here is one of supply and demand.

We have a supply of literature going back hundreds (and in some cases, thousands) of years. Still, it is continuously growing. Now at a rate higher than any other time in human history. Meanwhile, the demand for that supply is questionable.

I’ll be fair by using myself as the first example. Personally, I read less than ten books last year. I was pretty busy.

I go to a university program filled with teacher candidates. Educated people. When asked about what books they recently read, one of the prospective English teachers lists nothing but video games, with the argument that they count as texts. They do. This doesn’t at all nullify that this person, who will soon be teaching English lit, does not pleasure read. They’re a great person, and they get a lot of my nerdy references. They also probably understand even better than I do the ultimate impact of having students read literature as a form of labor. Of demanding it of them.

“Your homework tonight is the arduous task of reading a chapter of The Great Gatsby.”

The students then groan as they are forced to bury their noses in one of the greatest works of American literature. From here on out, they will remember reading as work, forced on them by overeager English teachers demanding that they understand concepts far beyond their limited life experience.

Though I suppose that’s an unfair generalization. When presented by a good teacher, a number of students will enjoy it who wouldn’t otherwise. When presented by a bad teacher, there may still be some who still enjoy it. They’ll all go on to become English majors.

And I was an English major. I read less than ten books last year.

I have another friend who writes books and self-publishes them. She hardly makes any money, and her books are short and fun for her to write. She is, in a sense, a hobbyist. Ten years ago, when I was younger and prideful, I would have felt disdain for this. Told myself that my books, which I work on for years and then submit to literary agents so that they will be rejected, come from a true dedicated artist. Now, though, I begin to wonder if she is a better writer for this era. Her books are finished, after all. They’re available on the market. I sit here staring at my screen, perfecting my work that will not be read. I offer it to people for free. It still is not read.

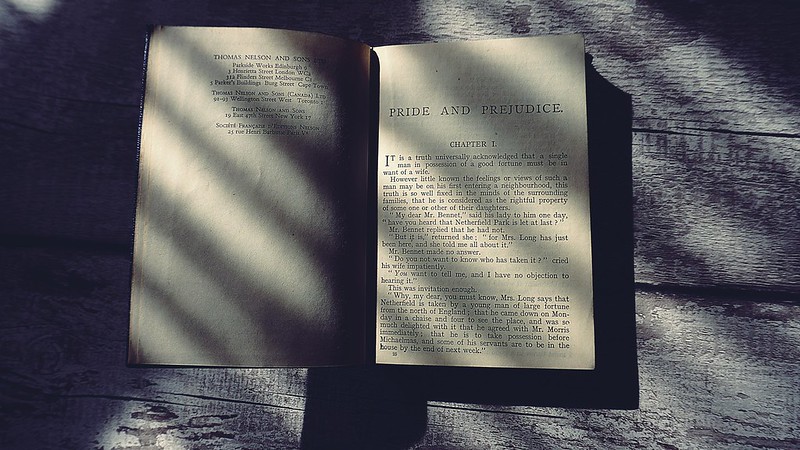

I think this as, when I have free time, I tell myself to read. Tell myself that, as a writer, it’s good for me. What if I wasn’t a writer? Where would be my motivation? How, then, can I ask someone to read my novel? When netflix is always on with a negligible monthly fee (If you even pay for it)? When Hulu doesn’t even charge if you tolerate ads? When social media offers all the reading you need and then some? Who wants to engage in the crusty, Victorian act of opening a five hundred page novel, reading the first page, and then reflecting that you have four hundred and ninety nine more to go?

Some of my poems have been published. Outside an open-mic, this impressed a young adult who hadn’t graduated college yet.

“So what’s it like?” he asked me.

“What’s what like?” I asked him.

“You know, being Published [Capitalization for emphasis].”

I stopped and had to consider this.

“It was an online publication and I linked people to it,” I said. “Pretty much no one read it.”

He stared me down, trying to decipher the brilliant secret of my Success, and why it didn’t sound very Successful.

“So…you can just have your work accepted now, anywhere?” He asked. “Like, people want to publish you now.”

“Not really,” I said.

“What?” He said, casually, as his views of the rewards of writing were altered by my terrible, honest example. “Ah man…Are you serious?”

The Solution(s)(?):

Change how you think about writing.

I’m going to tell you right now: fuck the dream of your name showing up in the bookstore. Barnes and Noble is the only successful bookstore chain and it’s because they branched out into coffee, board games, and nerd iconography. The books alone were not a profitable venture. And everyone with their work on those shelves is the equivalent of celebrity. They won the lottery like every celebrity does.

You could self-publish on Amazon, I guess. I just have a question: Is the villain of your sci-fi novel a monopolistic corporation that is rapidly developing ethically questionable technology which it then uses to “advance” the world toward a dystopia that eschews basic human rights? I’m just really curious.

I’m sorry, that was slightly off topic. But I’m not editing it out.

Back on topic: I’m trying to pick up on these hopeful tidbits around me. I’d recommend that you do the same. The first of those tidbits is that people like stories as much as ever, and books are still a rich source for them. Shortly after the clumsy, at times laughably terrible ending of Game of Thrones, another tv series rose to prominence based on a popular (albeit translated and already multimedia) fantasy book series. You probably know what it is by now. Likewise, there seems to be an expanded universe in novel-form for everything these days. So prose-writing doesn’t seem as though it is actually going to die. Statistically, book sales are as high as they’ve ever been, perhaps higher. It’s just that those sales tend to be highly concentrated. Like how everyone reads Harry Potter. But no one has read Charlotta.

You: “What the hell is Charlotta?”

Me: “I wrote that.”

You: “Oh. Don’t send it to me, please.”

The second tidbit is that you are free. So long as you are writing fiction, you do not need to sell out. Why?

You won’t make money even if you do.

I asked my friend who works a corporate job how much money he would need to be paid in order to do something he didn’t care about. He was immediately irritated at this question. The arrogance of this novelist, he must have thought. Demanding that he write what he wants to write instead of what the market wants.

“Anything,” he said. “I’ve been working jobs I don’t care about my entire life.”

I repeated: “But how much would you need to be paid?”

He grew more frustrated. “Anything, as long as I could live.”

“How about $30,000 a year if you’re lucky,” I said.

This stopped him. Someone else admitted: “That’s not enough to live off of.”

“It’s not.”

“What about Brandon Sanderson? He writes conventional fantasy stuff,” the same friend asked.

“Brandon Sanderson is a trendsetter,” I had to tell them. “Brandon Sanderson is a celebrity.”

There’s an urban legend running around that romance novelists make money. It deserves to be addressed. Romance novelists do make more money. Though look up the average earnings of romance novelists and you’ll find a bunch of “get-rich-quick” themed articles that are written with all the charm of a pyramid-scheme playbook. One of these articles will grudgingly admit that half of the romance novelists they surveyed made $10,000 a year or less. “BUT SOME OF THEM GOT RICH!”

Write your romance novels if you genuinely enjoy doing so. You can make a decent living off of it, and yes, you’re more likely to do so than an author of any other genre. Alternatively, if you are “writing fiction for the money,” try getting a higher-paying job doing pretty much anything else.

For so long, I personally felt constrained by the pressure to sell out if I wanted success. I realize how bullshit that is, now. In truth: there is no profit to be had, here. Write your dream novel. Or don’t write at all, I guess, if you just need to be paid for it. Measure your success in a different way.

The third tidbit that is helping me is the knowledge that we have not adapted to the post-online economy fully yet. There is a better way to get literature into people’s hands that has not been discovered. Or maybe there are better ways that already exist that haven’t taken off yet. As a mini-example, audiobooks went from being a fringe accessibility aid to a powerhouse with the rise of the Podcast. Which, by the way, is a platform that has successfully rescued the entirely dead medium of radio plays. If those can come back, God knows what else can.

As the Editor-In-Chief of The Metaworker, I’ve played around with what makes online literature platforms “successful.” If I’d figured it out, there might be thousands of people reading this right now. Not…well, y’know, like ten. But I am playing with it. I do have my finger on the pulse of it more than many people do. And what I’ve learned is that it’s batshit. People get degrees in this, and I understand why. I continue to see people producing online content who are not doing quite what we’re doing, but who speak to me of possibility. If you can take the oldest, dustiest medium and reinvigorate it for the social media, internet-driven age…well, that’s what we’re still trying to figure out. You’ll know when we get there.

In the meantime, I guess I’ll write, and be an English teacher.

It sounds like insanity, doesn’t it, though? With all the things I listed in the beginning. All the brutal discouragement and the realization that a lot of people can count on their friends and their family to be interested in their art, and many fiction writers can’t even count on that. Reading is hard. It’s also valuable, which is why I want to teach it.

But maybe it will lead to a valuable culling. I mean, it is true. When it comes to writing, supply outpaces demand. The rational response is to bow out, so many people will. And we, the crazy ones, will remain. When they ask us why we’re here, we’ll furiously type “I DON’T KNOW” into our keyboards, then keep working on our novels while we struggle under the weight of student loan debt for our Creative Writing degrees. We’ll see neither financial nor emotional return until, finally, we look around us, and see that there are still some people who want to read. And we, the insane, will not abandon the prospect of giving them books.

Then one person will read it. And they’ll tell you that they loved it. Which will mean that in another world just as large as yours, it’s special. Maybe not as special as it is to you, but still special.

At this point, that’s all you get. And if that’s not worth it, get out.